PART ONE

Thomy Lafon was a philanthropist and anti-slavery activist who helped found the Underground Railroad , the American Anti-Slavery Society and the Friends of Universal Suffrage. He was born in 1800, of blended ethnicities, and classified as a free man of color under Louisiana’s caste system. Fluent in French, English and Spanish, Lafon became a talented merchant and real estate broker. He funded numerous causes such as Southern University, the Sisters of the Holy Family, Charity Hospital, St. Mary’s Academy and the Catholic School for Indigent Orphans. As a donor to Straight University he left $3,000 in his 1893 will, the equivalent of about $78,400 in today’s currency the impact of which, in that time, was far more relevant than that amount would be today. Thomy Lafon was honored with the establishment of a school on that campus.

Thomy Lafon died at home in Faubourg Treme on December 22, 1893 and was buried in St. Louis Cemetery #3.

It should not be surprising that Thomy Lafon possessed such acumen as a merchant and in real estate, or that he was so involved in community development, given his father’s history. His father was called “the pirate architect” by one author who stated that “In the chronicles of American history Barthélemy Lafon has no peer. No one else was so proficient as a pirate, a scientist, an architect and a gentleman.” Around 1800 Barthélemy Lafon joined the consortium of pirates/privateers headed by the brothers Jean and Pierre Laffite in Barataria Bay, their home base. He joined them as a partner and architect and a sort of judge among the freebooters. When not on the coast of Texas dispensing of plundered goods Lafon was in New Orleans, his political and architectural home. Without a formal education in architecture or city planning, Barthélemy Lafon left France about 1790 for New Orleans where he laid out neighborhoods and designed buildings and public works while in partnership as a pirate (or freebooter) with Pierre and Jean Laffite. He was truly an entrepreneur, a civil developer and generally a very learned man. After his death all of his assets went to his son Thomy who, along with his younger sister Alphee who became a Carmelite nun, were born to Modeste Foucher, a free woman of color and the infamous Barthélemy Lafon.

With all of his philanthropic and civic activities it is fitting that the first public school to provide wider education opportunities for the “colored” population in New Orleans was named to honor Thomy Lafon.

The Thomy Lafon School was actually three different schools, built and rebuilt over time with each phase having its interesting, sometimes tragic, story.

The First Thomy Lafon Public School

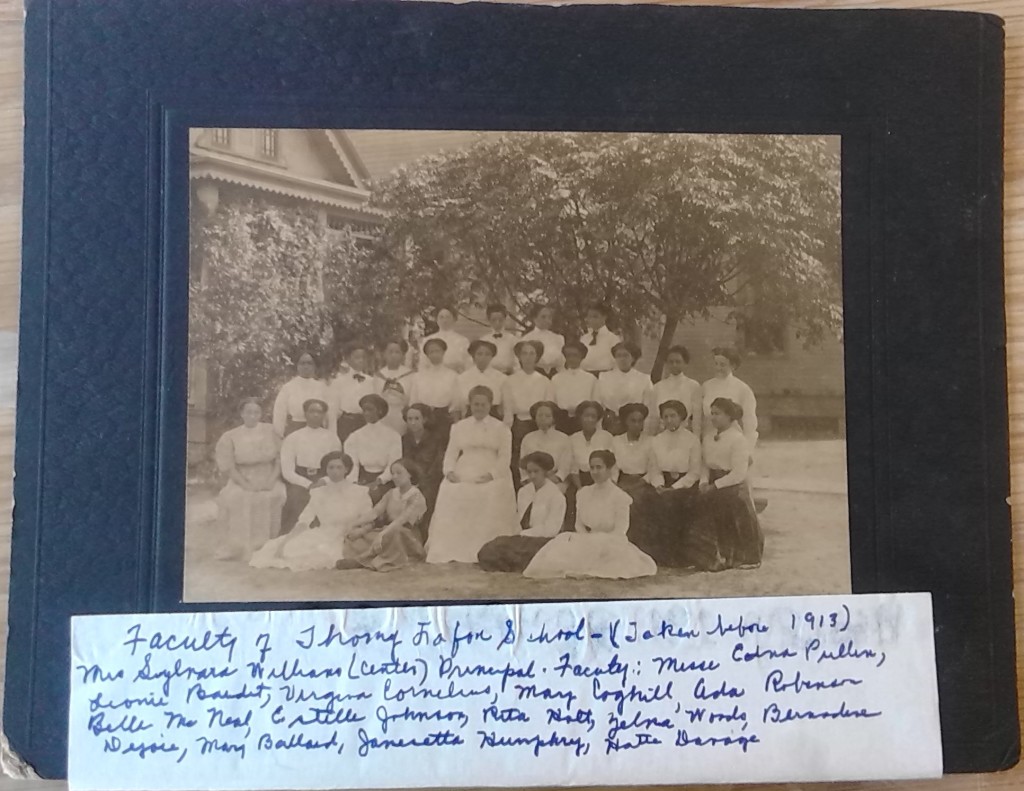

Completed in 1897, four years after his death, the first Thomy Lafon school was located on Howard Street between Harmony and Seventh Streets. The school was said to have been a large wooden structure and to have cost between $14,000 and $16,000. It offered grammar and primary school instruction. Its first principal was Sylvanie F. Williams, a widely respected writer and educator locally and nationally.

With the failure of Reconstruction and the rise of white supremacy in Louisiana in the late 1890s, the educational hopes for people of African descent were dashed. In 1900, white rioters burned the first Thomy Lafon school to the ground leaving 947 students without an educational facility.

(The Robert Charles race riot of 1900 was the result of an altercation between Robert Charles and his friends and three New Orleans police officers. Robert Charles came to New Orleans from Mississippi and was a self-educated, articulate activist. He believed in self-defense for the black community and encouraged black Americans in the United States to move to Liberia to escape racial discrimination. White citizens ended up killing Robert Charles but the mob that had been rampaging during the pursuit of Charles went on to kill random blacks and destroy property including the Thomy Lafon school.)

The fallout from this was catastrophic. Over the objections of black parents and activists, the Orleans Parish School Board halted all public education for Americans of African descent past the fifth grade. There would be no access to public high schools in New Orleans for black Americans until 1917.

An interesting fact about the Thomy Lafon school was that it was built on land that was a cemetery, then a waste dump and, later, declared sacrosanct because of the earlier cemetery and, therefore, could have nothing built upon it.

Locust Grove Cemetery

The Locust Grove Cemetery, or Potter’s Field, was initially located on Sixth Street between Locust and Freret Streets. It was a square of ground in which the pauper dead of the entire city of New Orleans were buried.

As early as 1868, citizens complained about the dilapidated condition of Locust Grove Cemetery. The fences were badly in need of repair which let cattle and hogs enter and it was overgrown with weeds. Citizens were asking for the repeal of the ordinance that created it.

In 1877 the New Orleans City Council passed an ordinance making a square (square No. 363) bounded by Sixth, Harmony, Locust and Magnolia Streets as a cemetery to be known as Locust Grove Cemetery No. 2.

In 1878 it was noted in a town hall meeting that the indigent who would normally be buried in Locust Grove Cemetery were henceforth to be buried in Washington Cemetery since recent rains drenched the grounds making it impractical to continue burials there.

Also in 1878, in a report to the Louisiana Board of Health, it was noted that “Having been used for many years, the same graves were made to receive the bodies of many dead—as many as six occupying a single grave!” The report went on to describe how the bones were raked and thrown out, with the coffin then being broken up and prized out. A new coffin was placed in the dirt mold of the old one. The dirt was then used to cover the new coffin…dirt containing body bones and skulls all heaped on the newest coffin. In 1877 citizens had presented a petition to the City Council in which they described the horrible conditions: how the stench in the summer pervaded their homes and that they were in dread of infectious and pestilential diseases whose victims were brought from all parts of the city and buried in their midst, making them fear for their lives. The 1878 report declared the graveyard an outrageous nuisance and recommended the selection of a site for a Potter’s Field in the neighborhood of the cemeteries, far in the rear of the city. The report also noted that the petition of the people fell on deaf Council ears and that a new square of ground was selected immediately adjoining the first. It noted that this new Potter’s Field (square #363 above) was a low marsh in which the sexton sometimes had to float the dead to their graves weighting them into their new homes, the whole graveyard often being a foot under water.

(As an aside, for anyone who may be doing research on this person, there is an article in The New Orleans Bulletin, May 29, 1875 regarding George Banks, a “colored youth” 19 years old, a native of Tennessee who supposedly died in the Small Pox Hospital in New Orleans of small pox. His body was provided with a certificate of burial and he was taken to the Potters Field—Locust Grove Cemetery—where, on the way, a witness saw that he was still alive. She saw his hand moving to remove the lid and that the cart driver put a pillow over his head to stop his movement. Apparently, poor George Banks was buried alive. He had been in a coma in the hospital but no one noticed.)

In 1879 the New Orleans Sanitary Committee hired a contractor at 27 ½ cents per cubic yard to fill in Locust Grove Cemetery but the city council decided to do it themselves. Locust Grove was filled up and no more burials were allowed.

In the second of this three part series about the Thomy Lafon school(s) more will be provided on the school and the toxic dump site.

Lenora A. Gobert–with gracious assistance from Keith Weldon Medley author of Plessy v. Ferguson The Fight Against Legal Segregation and Black Life in Old New Orleans. Keith can be found at http://keithweldonmedley.com/about.html .

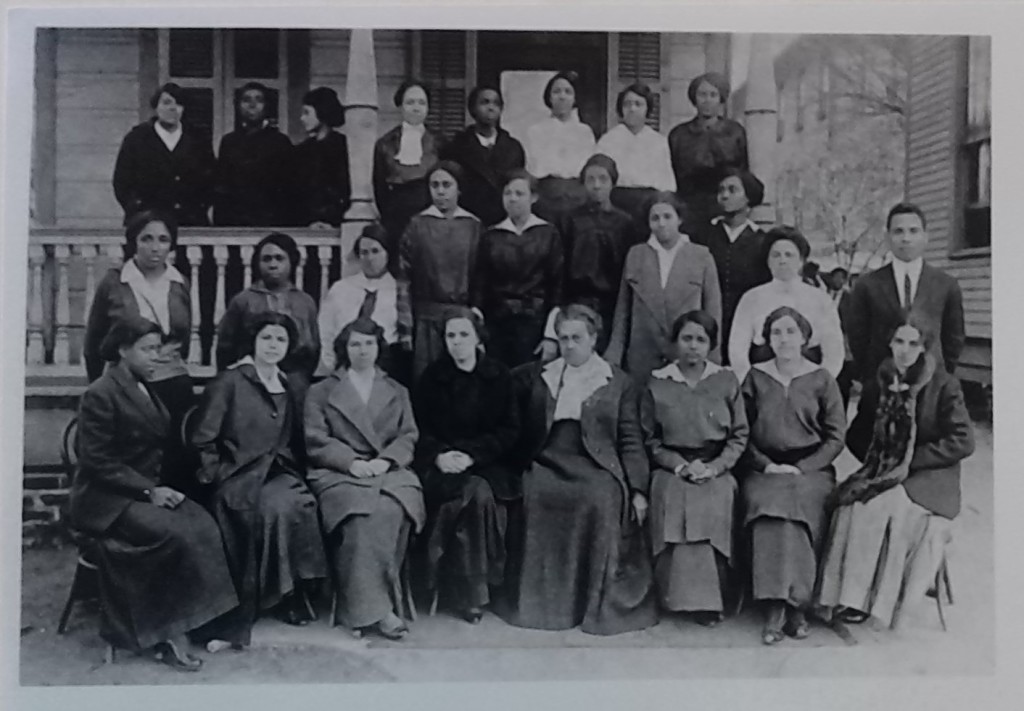

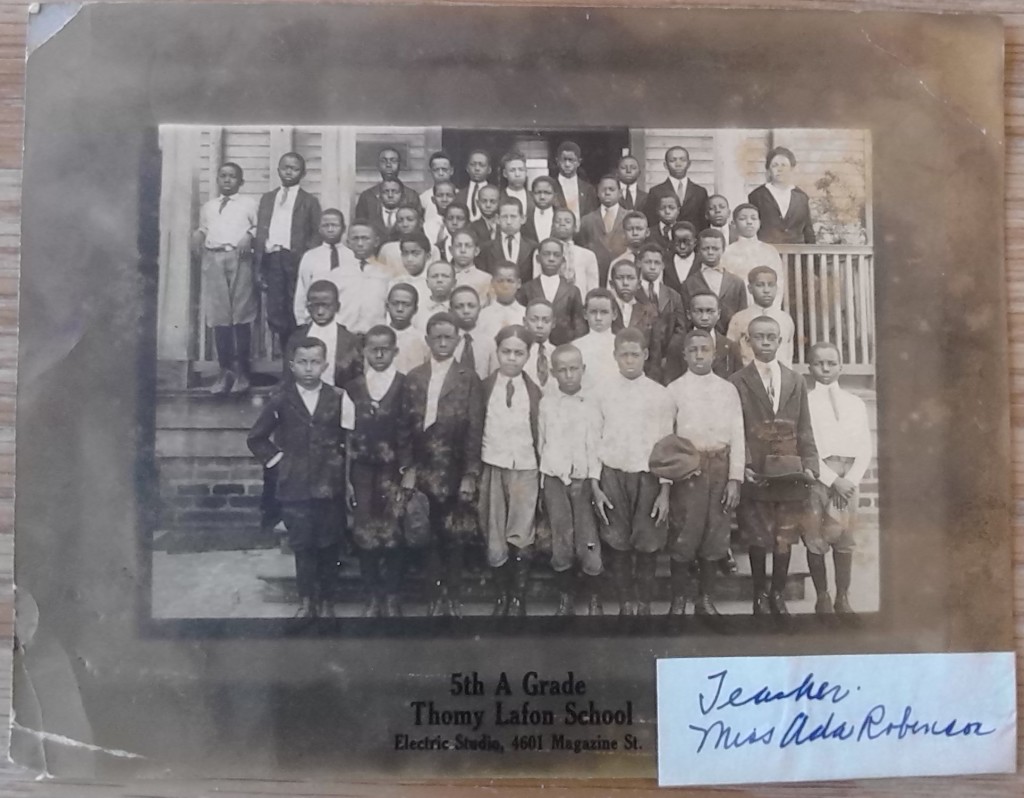

Sources: “Roger G. Kennedy: Barthelemy Lafon, True Tales of the Pirate Architect of New Orleans,” Architectural Digest, Vol. 50, No. 10, 1993,University of New Orleans Special Collections, folder OPSB 147, box 12; Wikipedia; “The St. Landry Democrat” April 12, 18979, “The New Orleans Bulletin” May 29, 1875 from the National Endowment for the Humanities Chronicling America; “Thomy Lafon Remembering the Legendary Creole Philanthropist on his 200th Birthday,” Ina Fandrich, La Creole; “The Daily Picayune-New Orleans,” July 28, 1900; Photographs from University of New Orleans Special Collections, box 12.

I live in New Orleans and never knew who all of these unknown people were that these schools were named after. I had no idea they were black.

Hi Carol,

The majority of our schools were originally named for very important men and women in our city who are heroes from our past. There is a book, “Names Over New Orleans Public Schools” by Robert Myers which contains the bio of these historical figures. The sad part is since Katrina and the establishment of our charter school system, most of our schools have been renamed and no longer give recognition to these individuals.

My grandfather Rev. Henderson H. Dunn taught at Lafon and Milne Boy’s Home.

Lived in New Orleans 17 years, attended Thomy Lafon school from 1970-1976. My mother attended Thomy Lafon 36 years earlier…my mother and I had the same first grade teacher Mrs. Lane, a solid educator. Miss NOLA life. Rory.

I am a member of the Plantation Revelers Club formed in 1939. Do you have any history of how and why the club was organized? Thank you in advance.

I attended Thommy Lafon Elementary, School from September 1961 – May 1968, which includes kindergarten – 6th grade. We lived across the street at 3207 Robinson St in the Original Section/Old Section ) of The Magnolia Projects.

I went to Samuel J Green Junior High School September 1968 – May 1971.

I graduated from Walter L Cohen Senior High School September 1971 – 31 May 1974.

I left New Orleans June 1974 for Howard University, and have not unfortunately returned to live since then.

I’m not 66 years old and frequently reminisce about My beloved hometown. I researched all the individuals whose names were on the schools I attended, as much as can be derived on the internet. All these institutions have produced GREAT INDIVIDUALS that were in derived from being educated in the NOLA public school system.

I like many who have expressed discontent with our schools being renamed and not allowing those historians names to live on and be recognized for their contributions. My primary focus is Thommy Lafon. Lucky Green & Cohen still exist. Lafon was rebuilt 3 times in the past. I hope and plan to get additional support to have it reconstructed in the near future.