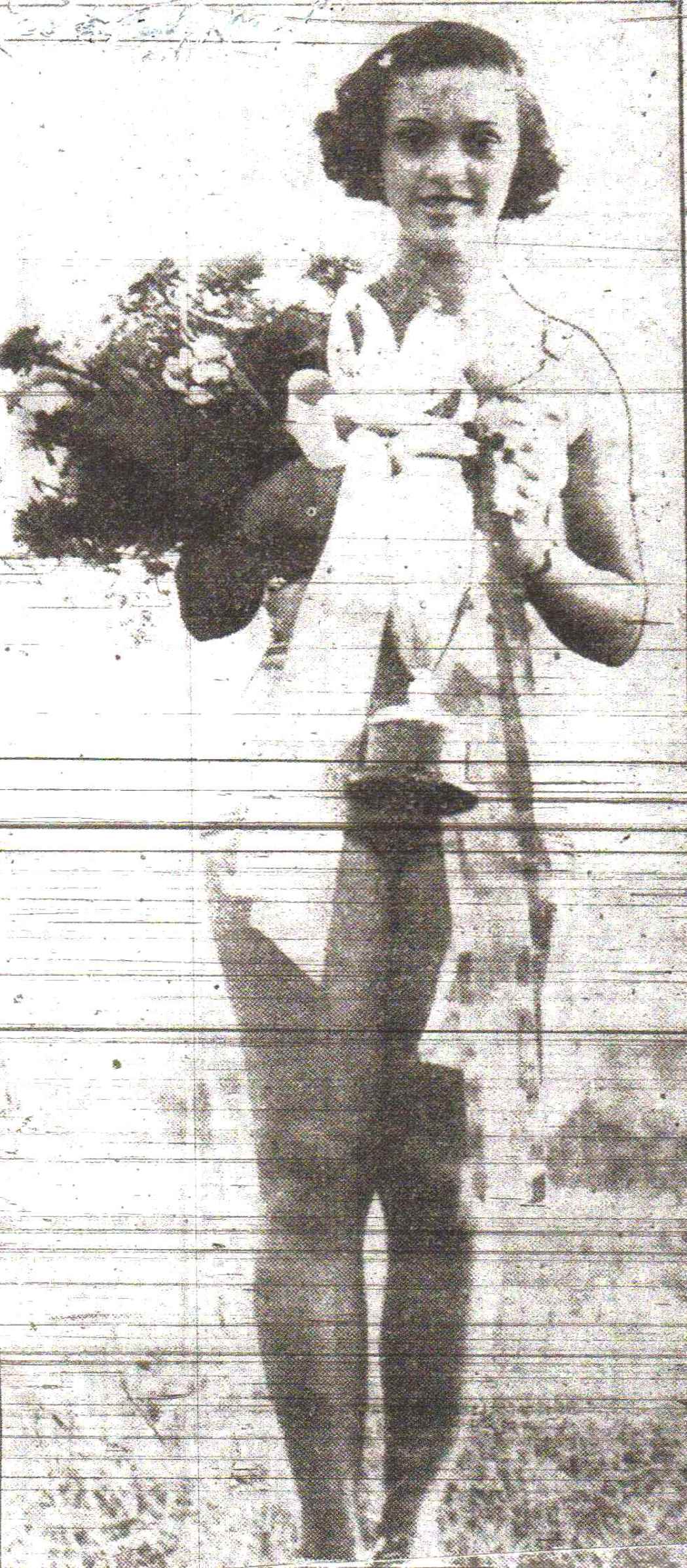

Helen Fernandez (Winner of first Bathing Beauty Contest at Seabrook- 1938)

Helen Fernandez (Winner of first Bathing Beauty Contest at Seabrook- 1938)

In the scorching heat and humidity of New Orleans during the summer months, many of us living here today seek shelter in our air conditioned homes, cars, jobs, and businesses. Unfortunately, that was not the case in the 1920s and 1930s. In order to cool off, New Orleanians had to gravitate to the lake. They sought refuge along the southern lakeshore area of the city to a small stretch of undeveloped land known as Seabrook . There, they would swim, fish, and hold family picnics.

Unfortunately, they were not allowed at the “white- only” Pontchartrain Beach, which was just a few blocks away and which opened in 1928; so they saw nothing wrong with claiming squatters rights for themselves on this little piece of the lakefront. Of course, they had not received permission to swim, fish and picnic here but, following the opening of Pontchartrain Beach and seeing the vast wealth of equipment the “white-only” beach was given, black leaders began making demands on the city. So in 1929, the city begrudgingly gave approval for them to stay.

This decision caused an uproar among the five neighborhood improvement associations in the lakefront subdivisions. Property owners flooded levee board meetings to protest the decision claiming that people of color would mar the beauty and value of their lakefront property. As a result, the city and levee board decided to make Seabrook so undesirable that no one would want to come back. So they refused to equip Seabrook with lighting, lifeguards, or concessions. They also started closing the site to swimming at the beginning of each summer. That soon stopped when the Urban League and the LA League for the Protection of Constitutional Rights threatened them with lawsuits.

In order to prevent lakefront homes from flooding, a seawall had been constructed in the area. As a result, the seawall caused rapid erosion and brought about the formation of dangerous sinkholes offshore. Pontchartrain Beach had sand brought in which extended into its waters and insured the safety of their white bathers, but it only succeeded in making Seabrook a more dangerous place to swim.

Reports of children and adults drowning or nearly drowning at Seabrook began to surface in newspapers as some swimmers were being sucked under and behind the seawall. Black leaders in 1932 attempted to force the city to provide lifeguards and police protection at Seabrook but, once the white groups voiced strong opposition, no action was taken. Darkness at night, lack of lifeguards, and sinkholes are a very dangerous combination when human lives are concerned.

Finally, a black businessman and owner of the Sea Side Inn, E.J.Lamothe, hired a team of lifeguards to perform the duties the city would not. Field trips for students,church picnics,plus swimming and water safety lessons were held to help curve the number of drowning deaths. Anyone who owned a truck or car could earn extra money bringing passengers to Seabrook in the summer months. Mr. Lamothe even sponsored the beauty contest that Miss Helen Fernandez (see above) won. This charming 17 year old was the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Walter Fernandez of 2658 Touro Street. She received a beautiful trophy, $25.00, and was sponsored by St. John Berchman’s Insurance Company. With all of its obstacles, many adults today have fond memories of Seabrook as a gathering place for their families and friends to unwind and have a great time.

By the end of the decade (1939), there was a determined effort to force colored people from the lakefront. Police officers rounded up and ran off black bathing parties from Seabrook. By July of 1943, a new policy was passed. Ordinance 16542 banned swimming at Seabrook and stated that all violators would be fined $25.00 or fifty days in jail or both.

The final blow came in the summer of 1945 when Mayor Maestri upheld the decision to prohibit bathing between the Industrial Canal and Franklin Avenue. This was also being done at the request of the military who now deemed it necessary to use the location to properly train soldiers and sailors in swimming and to prepare them in invasion tactics.

A 1944 editorial in the LA Weekly summed it all up.”It is a disgrace to the citizens to have it said that out of the many miles of water front around it, not one foot is available to Negroes. There is only one public pool. It is the Lafon Pool and it has been inadequate since it was built. Furthermore, it would take a very large pool to serve the almost 180,000 tax paying Negro people in our city.”

Once people of color were forced to remove themselves from the lakefront, there were concerted efforts being made to push them further down to a more remote location quite a distance away. An article in the LA Weekly in 1939 called it a”reptile-infested”portion of the lake which could only be reached by crossing dangerous railroad tracks. This new bathing beach would soon become known as Lincoln Beach.

Sources: Research on Lincoln Beach, taken from many of the same primary sources, has been published by Andrew W. Kahrl in his book: The Land Was Ours, African American Beaches from Jim Crow to the Sunbelt South, (published by Harvard Univ. Press, 2012); The LA Weekly, 7 July,1928 p.6; 14 July,1928 p.6;(photo) 3 Sept.,1938 p.1

Lolita V. Cherrie