The Black Republican was a weekly newspaper published in the English language in New Orleans, Louisiana from 1865 until an unknown date in the 1860s (most likely 1866). It was also known as the Weekly Black Republican.

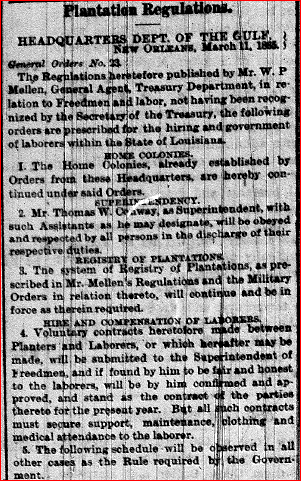

Informational ads were an integral part of this newspaper published after the Civil War to ensure that pertinent, timely information was brought to the “colored” population. It is interesting and helpful to step back in time to understand the climate in which our ancestors were living and how specific laws and regulations impacted their lives. For instance, there were “Plantation Regulations” issued by the Headquarters Dept. of the Gulf, in New Orleans, March 11, 1865 to wit:

“The Regulations heretofore published by Mr. W.P. Mellen, General Agent, Treasury Department in relation to Freedmen and labor, not having been recognized by the Secretary of the Treasury, the following orders are prescribed for the hiring and government of laborers within the State of Louisiana.”

The article goes on to give orders about the “Home Colonies,” an interesting post-Civil War economic construction.

The structure of Home Colonies is interesting and can yield valuable information. “After the Civil War, a major task faced by the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands was to help newly freed slaves adjust to their new lives. In Louisiana, the field office there established four “home colonies,” self-sustaining agricultural collectives that also provided schools, commercial stores, and a hospital. These colonies, the brainchild of the assistant commissioner of the Louisiana field office, Rev. Thomas Conway, were meant to be safe havens for persecuted freedmen as well as sites for training and educating them with the necessary skills for survival in post-Civil War Louisiana.

The Rost Colony in St. Charles Parish was by far the most successful of the four. The other three colonies, McHatton Colony near Baton Rouge, the Sparks Plantation in Jefferson Parish, and the Bragg Plantation in Lafourche Parish, never financially broke even as the Rost Colony did. The reasons for their lack of viability range from earlier claims by former owners for the return of the plantations to their lack of adequate medical and support facilities. Although the Rost Home Colony existed for only two years (1865 – 1866), the records created for tracking the lives of those freedmen fortunate enough to take advantage of its services have left genealogists with an invaluable resource. [The article written by Michael F. Knight (see Sources below)] examines the information found in the ‘Registers of Arrivals and Departures of Freedmen at the Rost Home Colony’ in the Records of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, Field Office Records for Louisiana (Record Group 105).

The two-volume register lists the names of freedmen laborers and heads of households at the colony, the names of their family members who accompanied them, the sex and age of each individual, date of arrival at the colony, and date of departure and destination. Also listed are the individual’s (or family’s) place of origin, former owner’s name, former occupation, familial connections to other groups or individual freedmen who arrived at a different date, and lists of subsistence stores (clothing, food, farming equipment) distributed to them. The register also contains assessments of the person’s physical or mental well being and general remarks further describing [him or her].

The Louisiana field office of the Freedmen’s Bureau divided the state into seven districts. Each district consisted of one to three parishes supervised by an individual with the cumbersome title of assistant sub-assistant commissioner (most often referred to simply as agents). The first agents assigned in 1865 were almost exclusively former Federal army officers who had served in the Civil War or active army officers. Between late 1865 and 1868, many of these officers mustered out of the service or returned to their original homes and were replaced by civilians deemed ‘of high moral character and organizational skills.’ Commissioner Howard and his headquarters officers were given nearly complete autonomy by Congress to create policy for the Freedmen’s Bureau. In turn, the assistant commissioners were given wide discretion to set field policies and administer their state operations.

The first assistant commissioner in Louisiana, Rev. Thomas Conway, used this power with great zeal. During the war, Conway had recruited black troops and supervised Negro laborers in Louisiana. In his brief role as assistant commissioner for the state, he pursued aggressive policies that proved extremely unpopular among whites in the volatile environment of postwar Louisiana. He circumvented the state’s newly reconstituted legal system by setting up special courts to hear cases of freedmen’s complaints, and he aggressively appropriated the property of former Confederate officers and politicians for bureau use. Conway directed that these confiscated lands specifically be used for the betterment of the freedmen’s conditions.

Judge Pierre A. Rost had been a high court judge in antebellum Louisiana before offering his services as an administrator to the Confederate government in 1861. He was assigned as the Confederate representative, or ambassador, to Spain for most of the war. On Conway’s orders, the Louisiana Freedmen’s Bureau seized Judge Rost’s house in New Orleans and converted it into two schools for orphaned colored children.

The bureau also seized two plantation properties belonging to Judge Rost. One of these plantations was the Rost/Destrehan Plantation in St. Charles Parish. The bureau designated this plantation as one of four “home colonies” in Louisiana for the protection and care of freedmen and indigent refugees.

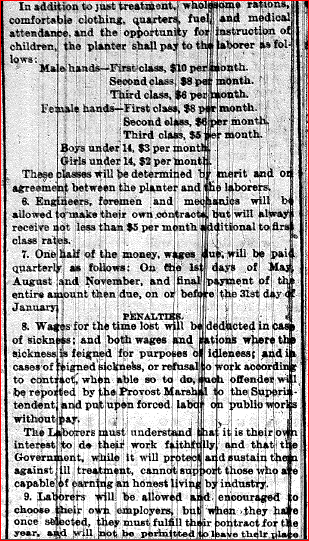

For those who have no concept of the skill level of former enslaved people, section 6 in the Plantation Regulations article lets us see the intelligence and skills of the freedmen where it says “Engineers, foremen and mechanics will be allowed to make their own contracts…”

This is activity that many of us are unaware occurred after the Civil War and should help broaden our understanding of the times in which our ancestors lived.

L.A.G.

Sources: Black Republican, 29 April 1865, pg. 2; archives.gov, Prologue Magazine, Fall 2001, Vol. 33, No. 3, “The Rost Home Colony, St. Charles Parish, Louisiana,” By Michael F. Knight.

Fantastic information. Keep it coming!

Thanks for this information… Do you know of any documents that would list the names of freedmen and indigent refugees who may have stayed at one or more of these “home colonies” in Louisiana, especially St. Charles Parish.

Patricia, aee the archive source at the bottom of the post. Go to it online. It provides much more information about the information you want and how to access it.

Lenora Gobert

________________________________