Adams, Elaine Parker. The Reverend Peter W. Clark: Sweet Preacher and Steadfast Reformer. Bloomington, IN: West Bow Press, 2013.

In The Reverend Peter W. Clark: Sweet Preacher and Steadfast Reformer, Dr. Elaine Parker Adams manages in just over one-hundred pages to effectively and coherently articulate three interconnected stories: the biography of a late-nineteenth century African-American minister; the story of a black family in post-Civil War/Reconstruction era South; and the history of black Methodism in Louisiana. Adams achieves this feat through feelingly-written prose based upon thorough research in a variety of archival repositories.

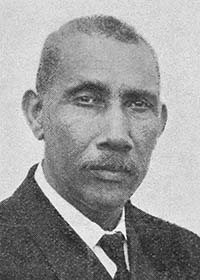

The ministerial career of Peter W. Clark, as described in the text using his many editorials and accounts of his work, was defined by a genuine care for the people under his charge. The work completely belies any notions of African American preachers as ill-prepared for ministry or lacking in devotion to their callings. The title alludes to an editorial written by Clark in 1894, in which he declared ‘Sweet preaching’ and no reformation of the lives of the people is no good.” For Clark, as a true Methodist, homiletic skill was to be cultivated and valued but only insofar as served to edify the faithful. As a circuit preacher, Clark and his family moved from one charge to another often, usually at intervals of two or three years, and at each he found a new field of endeavor. Often the author draws comparisons between the life and ethos of Clark and John Wesley, the eighteenth-century British father of Methodism. Both men shared a transcendent confidence in Divine Providence, a commitment to ongoing formation, and an embrace of ‘practical divinity.’

Drawing on census records, obituaries, newspaper articles, and a surviving family Bible, the author is able to give a detailed and compelling portrait of the Clarks’ family life. Peter Clark was born to enslaved parents in Port Hudson, Louisiana in approximately 1859. His earliest years were spent in slavery. His father, also a minister named Peter Clark, was of Virginia parentage and had at least two sets of children, thus Peter W. Clark had several half-siblings, including an older brother who entered the ministry.

The Reverend Peter W. Clark – Methodist Clergyman in Louisiana

The Reverend Clark lost the vast majority of the children from his two marriages to early deaths, most of which were due to tuberculosis, which was pandemic. His wife and children would have grown accustomed to frequent moves from the parsonage of one charge to another. At varying times, he welcomed into his household his wife’s younger siblings and other relatives. Though stricken by illness himself at times and undoubtedly saddened by so many deaths in his immediate family, he remained steadfast in keeping his hand on the Gospel plow, as an old hymn reads.

The author expressively recounts a family story marked by early mortality, extended family living, access to education, and itinerancy. The author pays particular attention to two of the Reverend Clark’s grandchildren, Mrs. Grace Clark Parker and Mr. Peter W. “Champ” Clark. Both longtime and legendary educators in New Orleans, “Champ” Clark is well-known as a poet and radio journalist during the era of segregation. He covered much of the area’s black prep sports and had a popular talk/music program on the local station WBOK.

Peter Wellington Clark (grandson and namesake) – Educator and Journalist

The story of Methodism, and indeed Protestantism, in general is one far-less studied in Louisiana than that of Roman Catholicism, the faith of the state’s French and Spanish colonial settlers. The author draws heavily upon articles and editorials from the Southwestern Christian Advocate and the journals of the Methodist Episcopal Church. As noted previously, Methodism was founded in the eighteenth century by John Wesley and others whose roots were in the Church of England. The Methodist Episcopal Church split over the issue of slavery in 1844, with the southern conferences forming the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. The vast majority of enslaved people thus were exposed to Methodism through this church. After the Civil War, the Methodist Episcopal Church (the mostly northern, anti-slavery denomination) sent its missionaries to the South working among the freedmen. These M.E. missionaries established churches and schools, including New Orleans University, so beloved by Reverend Clark, and Gilbert Academy. In 1870, the M.E. Church, South released most of its black members to the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church. Other blacks had previously joined the voluntarily segregated African Methodist Episcopal Church, founded in Philadelphia in 1816, or the smaller African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, founded in 1821.

For blacks who affiliated with the Methodist Episcopal Church, such as the Reverend Clark, they were organized into separate annual conferences along racial lines. The black Louisiana Annual Conference existed until 1971. Thus the researcher has to display added diligence in seeking out information about black clergymen and congregations, which often have fallen below the radar of historians of Methodism. Adams presents the story of the development of black Methodism clearly, offering ponderings as to why Clark maintained his denominational affiliation. The Archives of the Methodist Conference, including the annual conference journals, are kept at Centenary College in Shreveport with a smaller collection in existence in the Dillard University Archives. One of the most important sources for research is the Southwestern Christian Advocate (SWCA), a Methodist newspaper published at New Orleans from 1873 to 1929. While it certainly contained mission news and obituaries such as those consulted by Adams, the SWCA also offered a compassionate view on racial issues of the day. It famously contained a column, “Lost Friends,” which aided former slaves in locating separated family members. Among the editors of the SWCA were noted black clergymen Dr. A.E.P. Albert and Bishop Robert Elijah Jones.

All of these stories are contained in the volume masterfully written by Dr. Adams. The Reverend Peter W. Clark: Sweet Preacher and Steadfast Reformer makes a significant contribution to African American biography in Louisiana, to the field of black genealogy, and to the state’s religious history. The life of the Reverend Peter W. Clark is embodied by service to the people of God and trust in God’s abiding love. The concluding words of the text, taken from those of Peter the Apostle and which the author applies to Reverend Clark might very well be related to the whole of the black Christian experience “though now for a little while you may have had to suffer grief of all kinds of trials, these have come so that the proven genuineness of your faith … may [be] revealed.”

Readers may obtain copies of The Reverend Peter W. Clark – Sweet Preacher and Steadfast Reformer by visiting West Bow Press or Amazon.com.

J.C.L.H.

This book has answered a multitude of questions that I have had for the past 57 years. Thank you very much Dr. Elaine Parker Adams for your exhaustive research. I will always cherish what you said in 1963 at the Tennessee Williams adaptive play-The Glass Menagerie-La Petite Theater in the Vieux Carre-French Quarter of New Orleans…….If a Man’s or Woman’s Grasp does not exceed their reach-What is Heaven for? We need more awareness of the contributions of great men like the Reverend Peter Wellington Clark to unearth what really happenned in Louisiana after the Civil War. We look forward to your next book! Paul and Janice Clark Aurora, Colorado near Buckley Air Force Base.

I am the great- grandson of Peter Wellington Clark on my father’s side and AEP Albert on my mother’s side.