Probably like many of you, I wondered what happened to the country of Haiti (formerly the colony of Saint-Domingue) after its Revolution. I became even more interested when, in the course of my family history research, I learned of the influx of Saint-Domingue Creoles and slaves and that many Americans went to Haiti when racism in the United States became too much for them to bear. Seems that all we ever knew about Haiti was it was a poor country that, for some reason, remained poor. Like me, you may have had a lot of questions about what happened to this country or why we never heard or saw much about it until the “boat people” refugees began arriving and then the earthquake in 2010. “Haiti: The Aftershocks of History” by historian Laurent Dubois should answer all of your post-revolution questions about Haiti from Dessalines to Duvalier.

Even before the 2010 earthquake destroyed much of the country, Haiti was known as a benighted place of poverty and corruption. Maligned and misunderstood, the nation has long been blamed by many for its own wretchedness. But as acclaimed historian Laurent Dubois makes clear Haiti’s troubled present can only be understood by examining its complex past. The country’s difficulties are inextricably rooted in its founding revolution—the only successful slave revolt in the history of the world; the hostility that this rebellion generated among the colonial powers surrounding the island nation; and the intense struggle within Haiti itself to define its newfound freedom and realize its promise.” [book jacket]

Dubois brings into this story of struggle people from many nations who made Haiti their home. “…Haiti at this time was a magnet for immigrants. In addition to African Americans drawn by [the Haitian] travel subsidy, men and women from Germany, Corsica, Syria, and other countries came to Haiti in significant numbers during the second half of the nineteenth century.” [pg. 112] “An organization called the Haitian Bureau, funded by [the] government with $20,000 (the equivalent of about $500,000 [in 2012]), set up offices in several U.S. cities, including New York and New Orleans, and brought more than two thousand American emigrants to the country in the early 1860s.” [pg. 154]

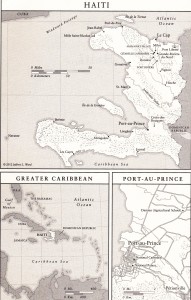

Most probably do not know that the United States, flexing its muscles as the growing power in the Americas, first wanted to annex Haiti and finally decided to invade and occupy the country in the early 20th century, from 1914 to 1934. The U.S. occupation of Haiti controlled it both militarily and economically, establishing rules and institutions that centralized power in the city of Port-au-Prince, further alienating the majority of the population which was rural. The U.S. occupation also exacerbated the centralizing of power created by the constant coups led by whichever strongmen came into power.

Medical doctor Francois Duvalier came to power after watching various coups and foreign powers jostle each other over trying to master Haiti to exploit its potential economic riches. “Papa Doc” Duvalier managed to stay in power because he was able to out maneuver the United States. “At the time, Washington’s approach to Haiti was…uneven and fragmented, with different actors—the president and Congress, the State Department and the diplomatic corps in Haiti, the CIA and the U.S. military—each pursuing their own agenda. Duvalier understood that, and he also understood that the broader Cold War context provided him with ample opportunities to manipulate the U.S. government to his own ends.” [pgs. 333-334]

Ricardo Seitenfus, the Brazilian head of the OAS (Organization of American States), said in 2010, “’Haiti’s original sin, in the international theatre, was its liberation. Haitians committed the unacceptable in 1804.’ The world “didn’t know how to deal with Haiti,” and time and time again simply turned to force and coercion.”

In our search for answers to our ancestral stories we have begun to understand the impact Haitian Creole and slave immigrants had on south Louisiana culture. I strongly recommend this work to those who wish to understand the forces, both internally and externally, that shaped Haiti as we see it today.

Lenora Gobert

creolegen@yahoo.com

-is the best email to contact directly and not

posted? have personal info to share.

thanks

GJohns

If it is information our readers can benefit from please post here. Otherwise you can email me at lenoragobert@yahoo.com

Sue Jane Mitchell’s fahter – and after he died – her mother were Ambassadors to Haiti. She probably has a lot of information about the country because they were in that position for many years.

Several people high up in the Haiti govment visited New Orleans many times. I know of those between abou 1950 and 58.

Sue Jane is still in New Orleans. I don’t have her number, but she shouldn’t be too hard to track down. She worked at Dillard University for a time and I believe lives in the area of Dillard.

One of my grand aunts was from Haiti. I recently learned from one of my father’s cousins now 96 years old, that my great grandmother’s 1st language was French or Creole French. That she didn’t teach any of her children (my grandfather included) French. I remember that my father would have to repeat whatever she said to me. As a very young pre-school child I didn’t understand why that was the case.

I also heard stories about Haiti being punished for breaking the tradition of slavery and gaining their freedom, and was boycotted and despised by the colonial powers and the USA. That Haiti also had to pay France a very large sum of money after something like a World Court found them guilty of illegally taking “property” from France. That “property” being the hundreds of thousands(?) of African enslaved people who were freed by The Haitian Revolution. As one of the old people use to say: “We must be in the last days of this world, As the truth is coming out from under the covers to be seen by all”