The 4th floor of the Earl K. Long Library at the University of New Orleans contains an untapped trove of black history, written and compiled by a local poet and historian, whose work has been neglected by all but a few in the black community. It is known as the Marcus Christian Collection.

Born in 1900, Marcus Bruce Christian was the fourth of six children whose childhood was spent in Mechanicsville, Louisiana, now a part of Houma. Tragically, he lost his mother, Rebecca Harris Christian, when he was three and his twin sister when they were seven. His father, Emmanuel Banks Christian, was a labor union organizer for sugar cane workers as well as a teacher in the public school system for over thirty years. His grandfather, Ebel Christian, a former slave, became director of the Lafourche Parish public schools during Reconstruction.

Learning was paramount in the Christian household. Each night, Emmanuel Christian read poetry and other literature to his children. “One of my earliest remembrances I have of my father,” wrote Christian, “is of being perched upon one knee and my little twin-sister on the other, while he read French poetry to us amid screams of childish laughter.” As a result, Marcus developed a love for the written word, especially the works of such greats as Longfellow and Alfred Lord Tennyson. Unfortunately, his education ended at the age of thirteen when another tragedy struck, the death of his father.

Having lost both parents, Christian was forced to quit school to help care for his siblings. He worked in cane fields for seventy-five cents a day and later as a yard boy and general handyman in a town nearby receiving five dollars a month and board.

At the age of nineteen, he moved his brothers and sisters to New Orleans. There he worked as a chauffeur by day and attended school at night. Though he lacked formal training, Christian was highly literate. He began writing poetry and, by age twenty-three, had composed a book of poems. By 1926, through concerted effort, Marcus managed to save enough money from his job as a chauffeur to buy a small day-cleaning business, the Bluebird Cleaners.

In the early 1930s, Christian’s business faltered and folded by 1936 amid the Great Depression. Refusing to go on relief, Marcus sought other employment. Local novelist Lyle Saxon helped Marcus become director of a special Negro unit of the Federal Writers Project located on the campus of Dillard University. Known as The Louisiana Negro Writers Project, it was created for black intellectuals, writers and artists under the WPA (Works Progress Administration). Its purpose was to provide jobs for these individuals; the Dillard Project was set up to record African American History, culture and folklore throughout the state of Louisiana. This particular project differed from others in the United States because it did not seek to collect oral histories of former slaves; rather, it sought to chronicle black history with hopes of constructing the history of the race in Louisiana

For the next 7 years (1936-1943) staff members, under the leadership of Marcus Christian, did extensive research primarily of the city’s 19th and 20th century newspapers and manually transferred this information onto note cards. They also made use of local archives, universities, public libraries and the Louisiana State Museum when allowed to do so in segregated New Orleans. These note cards were meant to be used for the publication of a book written by its director, Marcus Christian, which would tell the true history of blacks in Louisiana. It would be called The Negro in Louisiana.

Christian remained part of this project until it was dissolved in early 1943. Arrangements were made to store all materials of the project with the Louisiana Library Commission at Baton Rouge. Christian, however, along with Dr. Albert W. Dent, persuaded Saxon to leave this material at Dillard thereby allowing Marcus more time to complete his book, The Negro in Louisiana, and the public would have access to all of its contents.

On January 12, 1943, President Dent hired Marcus to complete the manuscript covering the Dillard-WPA study of The Negro in Louisiana and to compile a catalog of the material collected with it to be placed in suitable filing condition. The target date for completing all this was June 1, 1944. Unfortunately, the work was never finished. President Dent offered Christian a position as assistant librarian at the university in 1944. Christian would remain in this position for the next six years.

From this time until his resignation from Dillard in 1950, Marcus’ interest in black history continued to grow. Marcus Christian had to resign as Dillard librarian because he had no college degree. Upon leaving the university, his collection was closed and stored upstairs in Dillard’s old library building. Storms would eventually damage the greater part of it beyond restoration. Fortunately, Christian had made extensive notes on the collection for his own personal use, including duplicates of the original note cards. Christian took them, as well as his manuscript history upon leaving the university.

After his resignation in 1950, Christian withdrew from all social contact. He became a recluse and retreated from writing. He worked part-time as a printer, then as a delivery man for The Times-Picayune newspaper. In 1965, at just about the lowest point in his life, Hurricane Betsy flooded his Lower Ninth Ward home. As Christian rushed to save his valuable collection from ruin, he was confronted by police and arrested as a looter.

“He sank into abysmal poverty and everyone lost sight of him.” stated UNO professor Joseph Logsdon. It was Dr. Logsdon, having had a long interest in local black history, who kept hearing the name of Christian as an authority on the subject. In the late 1960s, he located a post office box for Christian and arranged a meeting. Soon, the University of New Orleans did an unusual thing for a man with no college degree and created a special position. Christian spent the last six years of his life as special lecturer and writer-in-residence at UNO.

At an age when most people were retiring, Christian re-entered the world he left almost two decades before. Enthusiastically, he threw himself into his classes in English and Black History. His UNO students were inspired, captivated and impressed with this unique individual, both wise as well as a gentleman from the “old school of thought.” Students constantly stopped by his office as he shared countless stories, history and read his poetry out loud. He was never too busy for them as he typed on his manual typewriter, often dressed in a suit jacket with unmatched pants. To them he was wise, persistent, articulate and sometimes shy with a strong love for Louisiana (especially New Orleans) and a strong sense of racial pride in his work.

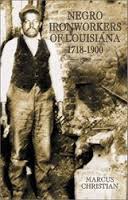

Negro Ironworkers of Louisiana 1718-1900

Although “The Negro in Louisiana” still awaits publication, Christian was the published author of both historical and poetical works. While at UNO he completed Negro Ironworkers of Louisiana, 1718-1900. Other published works over the years include The Battle of New Orleans: Negro Soldiers in the Battle of New Orleans; Common Peoples ‘Manifesto of World War II, High Ground and his longest poem, I Am New Orleans. Much of his poetry and historical works appeared in Crisis Magazine, Pittsburgh Courier, New Orleans States-Item, New York Herald Tribune, and the Louisiana Weekly.

“Christian gathered and hoarded information in the same way that a miser hoards gold. Unlike the miser, however, he intended to share his precious cache with others; unfortunately, he did not have enough time,” states Marilyn Hessler, author of Marcus Christian: The Man and his Collection.

In November of 1976, at seventy-six years of age, local black historian and poet Marcus Christian collapsed in his classroom. He died just a short time later at Charity Hospital. Coincidentally, his elder brother died at the same time. They were waked together.

Christian died without ever finishing the major work he had begun almost forty years earlier. He left behind an unfinished 1,000 page manuscript entitled the History of Blacks in Louisiana initiated during the period at Dillard under the WPA.

Why did a man so devoted to his race and its history never complete what would have been his legacy to that race? No one knows for sure. Maybe it was because he grew suspicious of many. He believed few cared what happened to him or his material. Colleagues tell of how he jealously guarded his work and wouldn’t invite alterations to it. A few, such as Attorney A.P. Tureaud, tried to raise funds within the black community in order to publish the manuscript. Christian himself even tried singlehandedly to publish his own work by mastering the art of handset type and printing, but with little success.

The Marcus Christian Collection was donated by the Christan family to the Archives and Manuscripts Department of UNO. This huge collection consist of approximately 245 linear feet of archival material scattered throughout twenty-five sections. Most of Christian’s papers, manuscripts, books and correspondence are housed here and it would probably take weeks, if not months, for one to cover its entire content. Within this collection are over 2,000 poems written by Christian himself, thirty-three boxes of articles known as the “clippings” section, twenty boxes of correspondence, thirty-four boxes containing his 1,000 page unpublished manuscript and fifty-five boxes of articles researched from the Dillard Project.

A tireless note maker, Christian even kept a diary that runs through four decades wherein he comments on almost everything he came in contact with from the seemingly trivial to the most pressing concerns of his life.

For a complete list of the entire collection, please visit http://library.uno.edu/specialcollections/inventories/011.htm#lis

As Marilyn Hessler states in her tribute to Marcus Christian, “The wealth of material deposited here stands as a memorial to a self-made man who devoted the major part of his life pursuing a dream which has not fully materialized. The scope of this dream will be evident when the full extent of his wide-ranging explorative unpublished material is made known”.

Sources: Marcus Christian: The Man and his Collection, Marilyn S. Hessler, The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, Vol. 28, No.1 (Winter, 1987) pp.37-55; Marcus B. Christian: A Reminiscence and an Appreciation, Tom Dent, Black American Literature Forum, Vol. 18, No. 1 (Spring, 1984) pp.22-26; Marcus B. Christian and the WPA History of Black People in Louisiana, Jerah Johnson, The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, Vol. 20, No.1 (Winter, 1979) pp.113-115; Memories of Marcus B. Christian, Deborah Parker Cains, (Chicken Bones: A Journal) http://www.nathanielturner.com/memories of marcus.htm; Marcus Christian’s Treatment of Les Gens de Couleur Libre, Violet Harrington Bryan, Creole edited by Sybil Kein, pp.42-44; I Am New Orleans & Other Poems, By Marcus Christian edited by Rudolph Lewis (Chicken Bones: A Journal) http://www.nathanielturner.com/biobibliographicalrecord.htm

Lolita V. Cherrie

Most impressive, inspirational and sad.Hopefully someone can create order from this wonderful legacy and prepare a book or an anthology for publication.

Of all the stories I have read at Creolegen I am most deeply affected by Marcus’: his strength, his faith in himself instilled by his parents. I am thankful for the work everyone contributes to educate about the entire history of New Orleans and Louisiana and beyond.

When will his poems be collected and released? There is the recent book of poetry inspired by Marcus Christian’s work: I am New Orleans : 36 poets revisit Marcus B. Christian’s definitive poem. If we want testimony to a life examined and lived to the full, I think Marcus has something to tell us, we need to be able to hear it so we can listen.