This post has been contributed by Mr. Lionel Khaton, a guest contributor to CreoleGen. It uses the life and heroic military career of Andre Cailloux as a window through which we can peer into antebellum New Orleans and the issues of color, freedom, and religion.

André Cailloux (pronounced Cah-you) was arguably the best known black hero of the Civil War. This was certainly true for the black community of New Orleans. He was born into the world as a slave and died as a free man of color in July of 1863 during the Battle of Port Hudson.

The conception of this article was originally intended to follow the informative style of many of the articles printed by this site; that is, to inform readers of notable persons from the Creole culture of New Orleans and the surrounding area. However, researching this article revealed some interesting social conditions extant during the 19th Century that are pertinent to problems we face today. Three particular elements will be dealt with herein.

The first is the social stratification based on color that exists in the Afro-Creole society. All historical references to Cailloux refer to him as a Creole and they all point out how he bragged on being “the blackest man in New Orleans”. This notion is contrary to ideas held by many who think color can be used to exclude one of Cailloux’s complexion from the ranks of Creole society. A basis from which to begin is needed so creole can be defined. Throughout the Americas, the word creole has been redefined over time for social reasons and has many meanings. It derives from the Portuguese word crioulo, meaning a slave of African descent born in the New World.[i] In her book Creole, Sybil Kein simply expresses it as any person residing in the state of Louisiana.

So, how does the stratification within the race take place? This social phenomenon seems far more prevalent in New World countries established by Latin language European countries, i.e.; Spain, France and Portugal. These countries created a new value system which was imposed on a blacks living in bondage. As these new Americans from Europe intermixed with the Native American and black populations they devised a caste system that placed a higher value on persons with lighter complexions. Hence, you get terms like mulatto, morani, high yellow, café-au-lait, quadroon, etc. Physical traits don’t become relevant in patterns of social superiority and inferiority until they are socially recognized and given importance by being incorporated into the beliefs, attitudes and values of the people in the society. Once this seed is planted groups within the race become stratified due to the desire to better their own conditions in life. So long as equality with whites did not exist as an option, many free people of color found it in their interest to maintain social distance between themselves and slaves in an attempt to protect their unique, if tenuous position in the tripartite racial caste system and to avoid sinking to the level of slaves in the eyes of whites.[ii] Anyone who watched the PBS series Black In Latin America by Henry Louis Gates will have noticed similar intraracial striations

The second issue is freedom. At some point André Cailloux became a free man of color, which brings us to the idea of freedom. No records exist to show how he got his freedom. We know his family had undergone several hardships and managed to pull together in the end. His father was a slave that was hired out and ‘highly respected’, as they say within the white community. André apparently adapted his father’s work ethic and managed to establish himself in a small business as a cigar maker. By this time he had become a stalwart figure in the Afro-creole community. But freedom for a black person in a slave society is an oxymoron. Many social dynamics were tugging at the fabric of New Orleans in the 19th Century.

Unlike other southern states, the Spanish had allowed blacks the right to take whites to court under certain circumstances. [Afro-Creoles like Cailloux had] unique access to the courts [that] was enjoyed by free people of color in New Orleans even in the midst of an increasingly hostile atmosphere, an access not enjoyed by most free blacks in states outside Louisiana.[iii] Louisiana had a myriad number of laws restricting black rights. At the same time there was integrated schooling in the city; although, other laws restricted black education to 5 years. Blacks were obviously trying to get a notion of what freedom was. They certainly knew it didn’t mean having the same privileges as whites. This pre-war environment is where André Cailloux built and maintained his reputation.

He was said to be a striking man who could deal with blacks and whites in a most professional manner. He spoke both English and French. Sometime between being set free and becoming a New Orleans artisan he had also managed to learn to write and was a member of the many civic societies that were popular during the time. He would have been considered middle class by our standards today. This had to be an awkward situation living in ante-bellum New Orleans as free man of color, yet, not really free. This quandary had to weigh on the minds of the many free people of color in New Orleans. This may have been where they began to form their ideas of what they must do to attain freedom. This struggle for acceptance is probably why Cailloux, along with numerous other free men of color, responded to the governor’s call to organize a militia regiment for the defense of the “Native Land” of Louisiana.[iv]

It’s interesting to note that the rank and file of the newly established Louisiana Native Guard consisted mostly of free men of color rather than the more plebeian conscripts one would normally find in such positions. Though Governor Thomas D. Moore authorized the regiment, it goes without saying that the Confederates would never allow a black fighting unit to engage in operations. Though some Creoles of color may have sympathized with the Confederacy, most, like Cailloux, probably joined the Native Guards with an eye to protecting or even improving their increasingly threatened civil and political status by demonstrating their loyalty to the state.[v] Since New Orleans fell to the Union early in the war, most of these men subsequently enrolled in the Union forces. Afro-Creoles also tried pressing the issue on moral grounds and the largest moral authority in the city was the Catholic Church. Surely God believed all his children were equal.

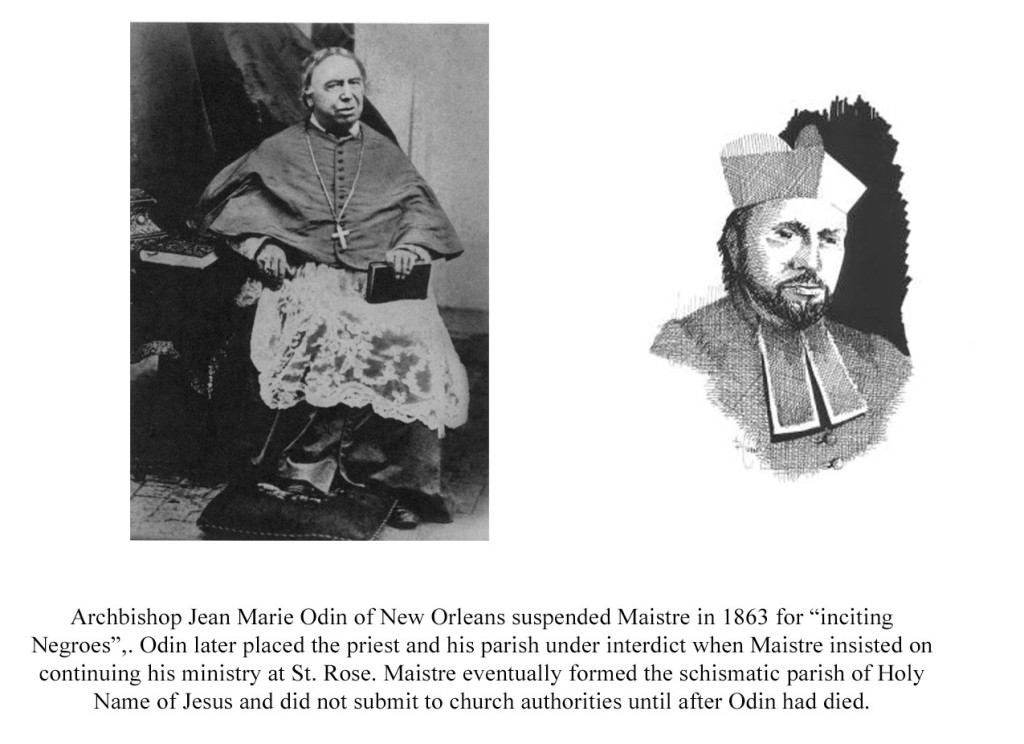

That brings us to the third issue that stands out in this research. The Catholic Church throughout the South wasn’t just steadfastly pro-Confederate; but, oppressively anti-black. During this time the Archbishop of New Orleans, Jean-Marie Odin, held blacks in utter contempt. Given the unabashedly racist white press and a suppressive Catholic authority it’s amazing that there are any black Catholics in the city. When a person feels seriously slighted by an institution in the white world, he will more than likely give up the institution. Martin Luther got angry with Rome and started Lutheranism. John Smyth started the Baptist Church, etc. Of course this hatred was entirely irrational then, as it is today. Masses at the St. Louis Cathedral were integrated; however, individuals purchased pews they would use during service. Initially, whites tried to bar blacks from the services and the archbishop consented until a boycott by Afro-Creoles caused him to back down from that practice. The name of a black father wasn’t written on baptismal records; rather, the name of a master or the priest was entered. Churches were originally integrated; however, as the city became more anglicized over time separate churches and congregations emerged.

There was one priest in the city who was quite progressive. He was Rev. Claude Paschal Maistre, a man with a dubious past. Father Maistre supported abolitionist views and freedom for all people of color. To a certain extent, he could be credited with having made André Cailloux a nationally known hero. He defied Archbishop Odin by conducting a public funeral service for Cailloux who received national prominence for his valor at the battle for Port Hudson. However, with the exception of Maistre, there were few clerics who viewed Afro-Creoles as equals. In July of 1863 André Cailloux became the first black hero of the Civil War.

News of Cailloux’s heroism reached the city before the captain’s body was returned to New Orleans. There was a long procession and thousands of attendees. He was buried in St. Louis cemetery. He became a legendary figure during the Civil War. His deeds were remembered and recounted often. He was often cited as an example by proponents of African-American soldiers serving in the Union Army. His story was printed in several northern newspapers.

After Cailloux’s death, his widow, Félicie, struggled to receive the financial benefits promised to veterans by the United States Government. After several years of effort, she received a small pension, but she died in poverty in 1874. She was working at the time as a domestic servant for Father Maistre, the Catholic priest who had preached the eulogy at her husband’s funeral

[i] Arnold R. Hirsch and Joseph Logsdon, Creole New Orleans: Race and Americanization, (Louisiana State University Press, 1992), 60

[ii] Stephen J. Ochs,A Black Patriot and a White Priest, (Louisiana State University Press, 2000), 87

[iii] Ibid, 58

[iv] Ibid, 68

[v] Ibid, 69

There are many kinds of Creoles. New Orleans Creoles, Haitian Creoles and French Creoles. The French Creoles are the designation for a French Citizen born outside France.

You’re absolutely right.

Excellent article. I would like to read how the culture of Antebellum New Orleans is correlated with contemporary issues in the Black community that was mentioned. Thank you.

Why, my oh my. Odin street in New Orleans is named for a racist bishop!….I prefer the Norse god Odin in any case.

I’m so “bienheureux” to share my name with André Cailloux. Lots of good André’s out there!!!! yeah, baby!

New Orleans Creoles were top society (French, Spanish, African mixture) until the English came to New Orleans and announced that those folks aren’t anything by N_____s and started the process of moving New Orleans Creoles out of top society. That is majorly how issues related to what is going on in the society today.

Mr. Orticke – don’t worry about Odin street being named for a racist bishop. What about Treme taking on the name of the plantation that pre-existed the naming of this community. Now there is self-hatred spelled out. It was not called Treme when I lived around that neighborhood. The Treme naming is more recent then that. That name needs desperately to be changed.

You really don’t know the history of Treme. Stop listening to those who think they know and find out yourself or from those who do KNOW.

I just saw your comment on Treme. First of all I am not a “mister” – secondly I was born and raised in New Orleans not far from what is now called “Treme” and it was not called Treme at all during my upbringing. I don’t have to listen to anyone, this history I know myself from 5 generations of New Orleanians – born and raised, all of them, and in the middle of everything that happened in New Orleans both on the White side and on the ‘so-called’ Black side and in the middle of Creole New Orleans. Your assumptions show your biases.

I should say to you, stop listening to those who want you to maintain a White history which is vaguely similar to and fits in with the Tara fantasies of whities. You are doing beautifully, I just hope others will see the incredible self-destruction of pushing forward and making over a section of New Orleans reduced, once again, to a plantation. That is the mentality and it needs to be changed – soonest.

The truth will clear out the fog in your post.

I grew up in the “TREME’ also.In fact my DAD was the iceman for that area.I only remember the area being called TREME. Would you share with me what the area was called before my time? (before1938)

THANKS

Hi Janice,

Disagreements can bring about amazing things. I knew the Duplantier family. I was raised in the 7th ward – probably within your time frame.

Lionel,

Excellent, well-written article. Thanx for sharing with me directly.

Excellent article and well written from a different perspective. Thank you for sharing it.

Andre Cailloux, paid the ultimate price for his family and community. He is my ancestor.

I would like to ask the author of such an informative article if this Cailloux is an ancestor of the Cayou family in New Orleans. I realize that many spellings changed over time and if this is one of them, he may be my ancestor.

Several years ago when I first looked into the Louisiana Native Guard and André Cailloux, I received an email from a lady in California who said she was related to Cailloux since her grandmother always talked about him. Unfortunately, I don’t have that communication anymore; however, I do know her last name wasn’t Cailloux. I just don’t know if there is a relationship. You might like to take the matter up with CreoleGen’s staff member, Jari Honora. I’m sorry I can’t be more helpful.

I have been trying to find his grave. Can you tell me where I can find it. I have been to both St Louis #1 and 2.

I’ve found out that he was buried in St. Louis Cemetery #2.

Also if there are any events concerning this hero

As of the time I wrote this article I was not aware of any present day events honoring this American hero.

There is a plaque on a society tomb in the second section of St Louis #2. Look left as you enter the 2nd section. I’ve read his grave was lost when the street was cut in and divided the cemetery.