Many of you, our readers, have written and commented on the article, “The Negro Einstein” which we posted on 5 May 2014. You have expressed your interest in learning more about Lucien Victor Alexis Sr., the Harvard graduate and beloved principal of McDonogh #35 High School for nearly 30 years. In response, I have written a follow-up article. This one is not on Lucien Alexis Sr. but his son, Lucien Alexis Jr. Although he may not have been as gifted academically and respected locally as an educator, Lucien Alexis Jr. and his journey at Harvard has made him just as intriguing and heroic as his dad.

Lucien Victor Alexis Jr.

Lucien Victor Alexis Jr. was born on 23 July 1921 to Rita Holt and Lucien Victor Alexis Sr. of New Orleans. Lucien Jr. was a quiet and polite child but always knew the high expectations set for him by his parents and the shoes he had to fill.

As expected, Lucien Jr. attended McDonogh #35 High School where his father, Lucien Sr. was principal. Upon graduation in 1936, Lucien ranked second in his class. “Lucky” (as Lucien Jr. was called) was accepted into Harvard at fourteen, but he persuaded administrators to allow him to first attend two years at the prestigious Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, the exact one his father attended previous to enrolling at Harvard.

Like his father, Alexis was not permitted to live in the dormitory at Exeter but was housed with the track coach, Ralph Lovshin, who was discriminated against not for being black but for being Catholic. While here, Alexis struggled and finished 213th in a class of 222. In a letter from Exeter to Harvard, he was described as among the “homo sapiens of mediocre ability.”

In 1938, Lucien entered Harvard, along with fifty-two of his classmates from Exeter. While here, Lucien’s freshman advisor wrote: “Alexis is pretty definitely ‘lost’ at Harvard.” A note on his transcript describes “a colored boy with inferiority complex (probably justified) – family feels he is a latent genius but the dean thinks he just hasn’t got what it takes.”

In the sea of white faces that was then Harvard, it was inevitable that two young men would find each other and would become fast friends. Both were from the Deep South—Alexis from New Orleans and Drue King from Tuskegee, Alabama. Both had their hearts set on becoming doctors and both loved the movies.

It was in this setting in 1941 that these two young men would put America’s oldest and most revered university on public trial that would continue to be written and discussed nationally even today.

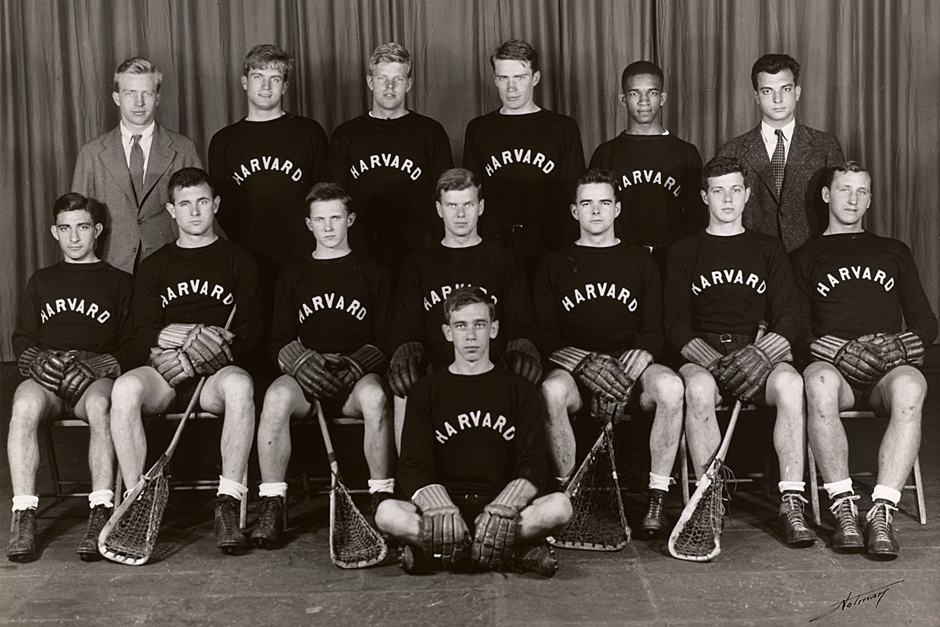

Harvard’s Lacrosse Team (1941)

Harvard’s Lacrosse Team (1941)

“Lucky”Lucien was now a junior, quiet, kind-hearted and the only black student on Harvard’s lacrosse team. Drue King, sophomore, good-humored and the son of Drue King Sr. (a physician at the Veteran’s Hospital in Tuskegee) was the only black in the sixty-man Harvard Glee Club. Both were looking forward to their upcoming spring break. Lucien Alexis would be playing against the U.S. Naval Academy and Drue King against Duke University.

On 3 April 1941, Harvard’s lacrosse squad arrived at the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. No sooner had the team arrived than all eighteen Harvard lacrosse players found themselves quarantined. The mess hall was cleared and Rear Admiral Russell Wilson was alerted. The admiral approached Harvard’s coach, Dick Snibbe, and demanded that Alexis be withdrawn. He would not allow his midshipmen to take the field with a colored man.

The Harvard team huddled in the field house debating what to do. Many were torn. To them, Alexis had never been outgoing and, many found him standoffish. None had taken the trouble to get to know him. To many, he was dispensable as a player.

Coach Snibbe refused to withdraw him. A social activist, Snibbe had made no secret of his contempt for segregation. It was now up to Harvard’s athletic director, William Bingham, to withdraw Alexis or forfeit the game. Bingham directed the coach to withdraw Alexis and place him on the night train to Boston. Alexis did not protest. He wished his teammates luck and suggested that the decision had been his. The next day, Navy crushed Harvard, 12-0.

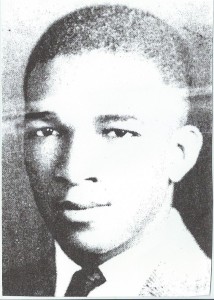

Drue King

At the exact same time, problems were brewing with the Glee Club. The hotel in Harrisburg, Virginia would not accept a Negro and another school fretted about King’s presence at a dance with white girls. But the most severe blow came when Duke University informed everyone that no colored man would be allowed to sing in its chapel. Again, the decision had to be made. Cancel the tour or abandon Drue King. On April 3, 1941, the Glee Club arrived at Duke University without King. He was dropped off earlier in Manhattan, said good bye to his classmates and wished them well.

Neither man wanted to return to an empty campus during spring break. Both ended up in Manhattan and surprisingly both ended up in the same movie theater. The two were overjoyed to see each other but spoke little of the events that had brought them together. For the rest of that week they hung out in movies and explored the city. They returned to Cambridge as if nothing had ever happened.

But they were wrong! Word quickly spread across campus as to what had happened. Many were stunned, angered and ashamed. Fifteen student leaders, one hundred faculty members, and many Harvard alumni members demanded that the Harvard Athletic Association never again bend to such discrimination. The New York Times, Associated Press and other newspapers wrote of what had happened and the NAACP demanded answers from both Harvard and Annapolis.

Finally, the Harvard Crimson accused Harvard of “kowtowing to Jim-Crowism.” Still Harvard refused to admit they had done anything wrong. Pressure continued to build. Finally, the Harvard Athletic Association announced that no one would ever be left behind again. On May 21, the Glee Club, by a vote of 55-8 banned discrimination. At this meeting, Drue King was elected vice president.

Harvard’s dilemma was known and discussed beyond its Cambridge campus. The following week, when the lacrosse team arrived by bus for a game at the US Military Academy at West Point, New York; black cadets were waiting to greet “Lucky’ Alexis, to offer their support, and to demonstrate that their academy was a cut above their Southern cousin.

In June of 1942, Drue King applied to Harvard Medical School. He was rejected. He spent the next years in the Army Medical Corps and soon returned to finish his last year at Harvard, where the registrar described him as a “colored lad, with a slight nervous tick.” He would soon attend and graduate from Tufts Medical School.

Drue King became an internist in Cleveland. Education remained important in the King family. One daughter, Judith, received her PhD from Columbia while Carol holds a doctorate from Kent State. King’s only son, Drue King III, graduated from Harvard in 1969. Two of King’s granddaughters also graduated from Harvard making the King family one of a select few black families to produce three generations of Harvard graduates. Another granddaughter, graduate of Duke, was invited to perform as a pianist. The event was held in the auditorium next to the chapel where her grandfather had been forbidden from singing.

Alexis did graduate from Harvard in 1942 and went into the service. Upon returning, Alexis was accepted into Harvard Medical School but then was told that he could not attend after all, because there was no other black student in the entering class and no one to room with.

Alexis then applied to and was rejected by Harvard Law School.

Alexis Jr. went on to Harvard Business School instead. On his application, he wrote, “ I have had no social life which would interest the committee. I have been admitted to no club and to no fraternity.” Even then, he yearned to be a doctor.

Upon graduation, he returned to New Orleans and married Rochelle Nash. He became the head of a small business school for black students which many New Orleanians remember as Straight Business School, located at 1234 North Claiborne Avenue. It was started by his father, Lucien Alexis Sr. and run by his mother, Rita Holt Alexis. It was a private school but was not a part of Straight University.

Eight years after Alexis was turned away from Annapolis, the academy graduated its first black midshipman, Wesley A. Brown.

In 2008, the head of alumni relations was an African-American who happened to have been a classmate of one of Lucien Alexis Jr.’s sons. The track there is named for Ralph Lovshin, the same track coach forbidden from being on the faculty because he was Catholic.

Lucien’s two sons, Lucien III and Llewllyn, attended Exeter, but neither went to Harvard. Decades later, he took them to the field house and showed them the photo of the 1941 lacrosse squad that still hangs on the wall.

Lurita Alexis Doan

Alexis had two daughters. One, Luchelle Nwakogba, left United States long ago to live in Nigeria. The other, Lurita Alexis Doan, a graduate of Vassar, is one of America’s most successful black businesswomen, founder and owner of New Technology Management Inc. One of its first contracts was with the US Navy—the very Navy that would not take the field because of her father’s presence.

Alex remained as private as he was independent. He built his home by hand and much of its furniture as well. He passed away on 4 February 4, 1975 (six years before his father) at the young age of 53. He was buried in the family tomb.

A white Harvard classmate of his, recalling the mistreatments Alex had to endure, wrote in 2008 “He and I belong to what has sometimes been called “the Greatest Generation.” If most of us have felt uncomfortable about the honor, it may be because we’ve known in some ways we haven’t been that great.”

Sources: The Boston Globe, Southern Discomfort- With quiet grace, two black men change the heart of Harvard in 1941, Ted Gup/ 12 December 2004 (provided by Harvard University Library); www.newyorker.com/talk/2008/11/17/08

Lolita V. Cherrie

My family lived next door to Lucien, Sr and Rita. I knew Lucien, Jr, but knew his parents much better. Lucien, Sr always carried an umbrella and was rather taciturn. As a boy, I always said hello anyway. He would acknowledge my presence and occasionally responded verbally. I remember engaging him in friendly pleasantries waiting for the Claiborne Ave streetcar. I didn’t know of his trials as a young man. I would have been taciturn, too. I left New Orleans after high school, and so knew Lucien, Jr mostly to exchange hellos when I visited later and he lived next door. Thanks for sharing their stories.

Interesting. This is a solidly written article that is both engaging and informative. It also reveals a part of New Orleans’ history that I wasn’t aware of.

My heart simultaneously weeps and feels great joy for these two wonderful black men for what they endured and accomplished. I can think of no other group that has had to live such a conflicted existence. In spite of everything, they kept their eyes on the prize. I can only pray that I possess but one tenth of the gravitas as they which they possessed.

Allen Kimble

I am a cousin of the Lucien Alexis family. My grandfather, Benoit Alexis was brother to Lucien Alexis,Sr. My mother was cousin to Lucien Alexis Jr. It is wonderful to read history of this part of the family. Hoping for more contact and shared memories with family members and/or neighbors & friends in New Orleans.

I went to elementary school with Lucien Alexis III at Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic School.

We graduated from 8th grade in 1968. That 13 year old boy was also taciturn and standoffish. His younger brother Llewellyn was similar. Speaks to the power of modeling in families.