In the novel Absalom, Absalom, William Faulkner famously described New Orleans as “that city foreign and paradoxical.” Forged in a unique cauldron, separate and apart from the nation’s revered original colonies, New Orleans’ Creole population has long elicited the interest of visitors and has been the focus of countless novels, plays, travel accounts, and orations. The stubbornness with which the Creoles held onto their unique culture, their clannishness and insularity in large part was never understood by their American neighbors.

The distinction maintained by the Creoles between themselves and the “Americans” met with the disapproval of two national leaders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) when they visited the city in the 1930s.

New Orleans is home to the oldest continually active NAACP branch south of the nation’s capital. The branch was organized in 1911 and formally chartered in 1915. The branch sought to raise awareness of racial injustice and did meet with some noteworthy victories, such as the 1927 U. S. Supreme Court decision regarding the illegality of residential segregation laws. In 1931, the branch successfully raised funds for a case (Trudeau v. Barnes) which unsuccessfully challenged the discriminatory practices of the registrar of voters.

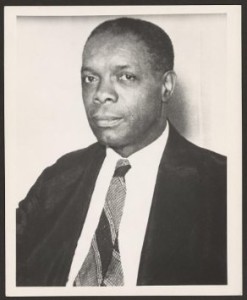

Despite these positive indications of effectiveness on the part of the branch, when Dr. William Pickens visited the city from June 17-18, 1934, he had words of reproach for the city’s black community. Pickens was a graduate of Yale and former dean of Morgan State College in Baltimore who served as Field Director with the NAACP from 1918 to 1941. Over the course of his two days in New Orleans, Pickens gave three public addresses – at the Pythian Temple to an overflow crowd; at the Chamber of Commerce; and at the Autocrat Club, to a much smaller audience, where his remarks were informal. In his speech, which was punctuated by humorous anecdotes and spontaneous applause, Pickens remarked that “I hear you are trying to have three races here in New Orleans. [In] most other places, we have trouble enough with two races, with three races here you must be having a regular picnic.” Interestingly, while the local black paper, The Louisiana Weekly, excluded that portion of Pickens’ address from its coverage, it was reported by Associated Negro Press and picked-up by other publications.

Given the edited version of Pickens’ remarks as reported by the Weekly and the fact that a small crowd was in attendance, it is possible that his comments did not cause much of an uproar. Four years later in 1938 however, when Walter White, another national NAACP official visited the city, he likewise commented upon what he saw as a useless division. Walter White was the Executive Secretary of the NAACP. “Negroes and Creoles maintain a division in New Orleans that is a definite hindrance to their progress.” White went on to say that “The Creoles and Negroes would have to stop fighting each other and fight together for those things that concern them as a combined group.” His comments were met with “murmuring objection” from the nearly one hundred social, professional, and business leaders who gathered to hear him in a banquet at the Rhythm Room.

Dr. Joseph A. Hardin refuted Mr. White’s comments in no uncertain terms. He defended the Creoles and argued that they had promoted cooperation and contributed more than their fare share toward making progress for the race. What is interesting, is that Dr. Hardin himself was not a Creole and in fact not even a native of Louisiana. Hardin was born in rural Scooba, Mississippi and moved to New Orleans in the 1890s in order to attend college. Hardin lived and worked however among many Creoles and was twice married to Creole women. Hardin’s response in defense of the Creoles met with boisterous applause from the audience. The entire incident however caused heightened tensions for several weeks, with much discussion from either faction.

The so-called “Negro” or American faction charged that up until a few years earlier the Creoles refused to send their children to Negro public schools, which accounted for “the little education prominent within [their] group.” There was also much discussion of the clubs and organizations among Creoles which excluded Negroes from membership. The Creoles charged the Negroes with “agitating an age-old assumption that [need] be discarded for mutual cooperation.”

While as a whole, the history of the New Orleans Branch of the NAACP and the record of the black community as a whole reflects many courageous strides in the area of civil rights, the age-old distinction between the Creole and non-Creole communities did exist and was called into question by these two national figures. Their remarks likely stemmed from a misunderstanding or lack of knowledge as to the historical background which shaped Louisiana and a monolithic understanding of blacks, with no account given to cultural differences.

Jari Honora

Sources: Sepia Socialite, 28 May 1938, page 1; Norfolk New Journal and Guide, 21 July 1934, page 20; The Louisiana Weekly, 21 May 1938, page 1.

Jari, a very interesting article: thank you for publishing it. It will take much thought on my part to completely process the information and try to see how this divide factors into the terrible legacy of intolerance that we all seem to share.

Indeed! The article is an accurate depiction of our people in New Orleans during earlier times and even as late as when I was a child in the early 1950’s. My father was a WW2 veteran who bought a large plot of land in the upper 9th Ward. When the city decided to build the Desire Project, eminent Domain required that we move. My family moved to 2915 Pauger Street between Miro and Tonti Streets. As an adult, I’ve lived in three different countries in Asia over an eight year period. Moving to the 7th Ward for me as a dark skinned little boy was as much a cultural shock as arriving in Vietnam, Japan and Turkey. The title “Creole” within our non-white community was a euphemism for being light skinned with straight hair. There was most definitely the desire, by many light skinned citizens to maintain the faux third race as talked about in the article above. If you’re old enough you might remember that some social and pleasure clubs would keep a hefty supply of “brown bags” at the door. If your skin was equal to or darker than a brown bag, you would not be allowed in. I have another particular recollection that I will be sure to share about my beloved 7th Ward and the peculiar system I found in moving their in the mid-1950’s. Thank for a most interesting article about our city and our history. Allen Kimble Jr.

I have heard your response to the Creole divide from others and find it particularly lacking in any knowledge about the Creole Community. A group of people with a different language, cuisine, etc. is a little beyond just a none-white community being light skinned with straight hair. Your response mimics the racist response of Whites to the Creole community. It allows them to deny its history, especially when you delve into New Orleans history you will find Creoles were at the top of society and were displaced when the English came and started to describe Creoles just as you describe them. That moved Creoles down the ladder since they were a mixture of French, Spanish and African. White Americans began to mix “Creole” and “Cajun” cultures and cuisines because they did not want to have to acknowledge any such mixture. I could go on, but I think a little study of history will correct your very copycat-racist response. One of the clubs which got the so called “brown bag” claim was the Autocrat Club. Since I lived around the corner and knew several gentlemen members who were relatives and quite dark, the facts of what you claim doesn’t match claims you are making.

Funny how people with this attitude to try and break down the Creole heritage, always go after the beautiful Creole girl/woman. Right?!!! LOL There is a difference with heritage, attitude, upbringing. Creoles were higher on the ladder in society. We did not struggle as the African Americans did. So right there, there is immediate prejudice and envy. To link us all together when we have a different genealogy and blueprint is really not the same distinction. Because of this pressure and trying to knock our culture and heritage, many Creoles were bullied by African Americans and told, “You’re no better. You’re JUST like us.” Eventually, more Creoles married African Americans. To this day, a darker man will always go after the light skinned Creole, mixed raced or white woman. Definitely there was an oppression with African American people. To be ranked in the classes also with Creole people, meant they were even more inferior. It’s understandable when the world operates on social class and privilege. Again, many Creoles married Black, but when their kids also marry Black (or any other race for that matter, over generations) although a French name may be present from history, to say you’re still a Creole is not true at all. At that point, you would just have had Creoles in your family’s past, unless (like MOST of my family members) we married OTHER Creoles. We can still say we are Creole, but many can’t at this point and time. The need to bash real Creoles is still going on, and the need to devalue our rich history is just plain ludicrous. Does that sound like jealousy to YOU? It certainly does to me!! Thanks for the article.

How is it known that Dr. Hardin was not Creole?

Dr. Hardin was born in Scooba, Mississippi to parents who were Mississippians on both sides. None of his parents were Creoles.

My mother was a New Orleans Creole, My father was biracial Mexican/Black born in Illinois and raised in Missouri. My parents met at Xavier University and eventually moved back to Saint Louis, where I was born and raised. This tension of African American/Creole divide was one that my mother taught us about, and taught us to reject. Our hair was neither good nor bad. It was simply hair. Our very black grandmother and white Mexican grandfather were simply our grandparents. My Creole New Orleans family was just family. We are all part of the Diaspora. Different languages, customs, food were always facts of our daily life, We have always identified as Black, because, regardless of color, that is what we are. But that is not all that we are. We live in a country that looks at us all as one homogeneous population. Class, color and subgroup do not shield any African American from discrimination.

This rebuttal is a crock. I was born and raised in the 7th ward and could rebut every point you made based on a life lived but I wont. I will say this one thing. Dark skinned Blacks were acceptable if they were the black sheep of an acceptable 7th ward family.

William Pickens and Walter White were right on.

Great article, very informative and full of issues for further discussion. Thanks.