James Guidry has submitted several articles to CreoleGen which dealt with his life growing up in Opelousas, LA as a young man. All of these articles have been extremely well written, thought provoking and very well received by you, our readers. But, in my opinion, this is his best one yet. In it, James continues his personal reflections of how history of the past has affected him as a person living in the present. Here he deals with a topic some may find morbid. Lynchings and the electric chair are hard to read about but they are a part of our history. It is important to insure that this part of history is never repeated again, and the only way to guarantee that is by keeping these stories alive. It is a little lengthy but, I guarantee you, it is so well worth every minute of your time. Please let us know what you think……Lolita

Lynchings, Gruesome Gertie and Coming of Age

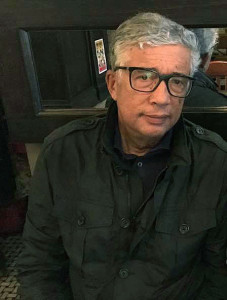

Atchafalaya Bridge at Krotz Springs

During the segregation era, black high school students traveled to Southern University for academic competitions. Our bus had to cross the Atchafalaya Bridge on US 190 at Krotz Springs. I would always remember the story my parents and their friends told of Honeycutt’s daring dive from that bridge to escape would be lynchers.

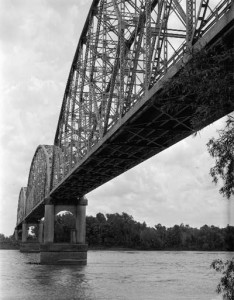

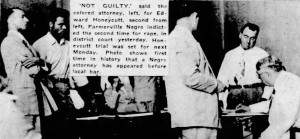

Edward Honeycutt

Edward Honeycutt, a 22 year old black man, was arrested for the rape of a white woman on December 1, 1948 in Eunice. The law had a signed confession the next day. Honeycutt was from Farmerville, La in Union Parish. Edward and his father had delivered a load of lumber to Eunice on the day that he was arrested. His father dropped him off at the bus station before returning to Farmerville. Edward wanted to purchase a ticket to Lake Charles to meet his wife. The clerk said he was too inebriated and called the law. They escorted him to the outskirts of town and told him to flag a bus. He was walking on the road when arrested. Edward was jailed in Opelousas, the parish seat.

Three white men abducted Honeycutt from the cell on the top floor of the three story Opelousas courthouse on March 6, 1949. It was a quiet Sunday night. The kidnappers’ version of the story is they drove Honeycutt to the banks of the Atchafalaya River. Honeycutt managed to free himself from the leather belt that bound his wrists while they matched nickels over who and how they were going to kill him. Stark naked, Honeycutt jumped into the river. He swam under water long enough to nullify the onslaught of bullets that followed. He made it safely to the opposite bank and eluded capture through the rest of the night. The ordeal left him somewhat disoriented. He was unable to effect a more permanent escape. A fisherman found him the next day. He was returned to jail. The black version of the story had a decidedly more heroic Honeycutt jumping off the bridge rather than the river banks. I don’t know which version of the story is true, but I do know the version I prefer.

Air raid bomb drills in U.S. schools (1950s)

The white citizens of Louisiana lynched 335 black men and boys from 1882-1968. White children had nightmares about nuclear war during the 1950’s. They covered their heads underneath desks during absurd school bomb drills. Southern black boys had fitful dreams of being lynched. These vampire nightmares drained the life out of our aspirational dreams and only disappeared at the first light of big day. Our nightmares had more of a reality base. Lynchings created victims in exponential proportion to the total number of individuals lynched. The image of Honeycutt’s dive off the bridge, real or imagined, created a kind of folk hero out of necessity.

Edward Honeycutt’s trial began in April 1949. He would be electrocuted if found guilty. The 1940 Louisiana Legislature changed the method of execution from hanging to electrocution. The effective date for the change was June 1, 1941 exactly 5 years before my birth. The state awarded International Harvester the contract to provide a portable electric chair, a truck for transport and a gasoline generator. International Harvester built a grotesque 300 plus pound contraption consisting of wood, leather and wires. The concept was to haul the killing device to local jails and courthouses where the condemned waited on the threshold of eternity. The inmates of Angola nicknamed this monstrosity Gruesome Gertie.

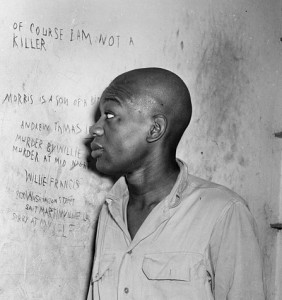

Gruesome Gertie

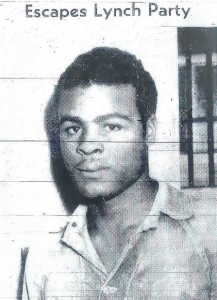

The cruel and temperamental punishment of Gruesome Gertie awaited Edward Honeycutt. It had been used in an earlier execution that was botched. The victim was 17 year old St. Martinville native, Willie Francis, who had been found guilty of a murder he almost certainly did not commit. The botched execution occurred on May 3, 1946 in St. Martinville. The state sent a semi-literate two man crew to perform the execution. One of the men was an inmate trustee. Their usual supervisor, the Angola warden, was not available. The two men spent the night before the execution in New Iberia on a drinking binge. They could be heard boasting about their appointed task before rapt audiences.

Next day, the executioners were still under the influence when they strapped Willie Francis into the chair. The chair was not grounded properly. It skittered in a ghoulish dance across the floor when the switch was pulled. Willie’s body convulsed. His lips protruded from the opening in the death mask. When they realized Willie was still alive, the witnesses yelled for more juice. The executioners continued to toggle the switch over Willie’s protestations.

Common sense finally prevailed and Willie was mercifully unstrapped from the chair and taken back to jail. Undeterred, the state scheduled another date for the execution of Willie Francis. His lawyers filed an appeal, Francis v. Resweber that went all the way to the Supreme Court. Felix Frankfurter cast the deciding 5 to 4 vote against Willie. Frankfurter’s conscience must have bothered him. He asked a friend to secretly contact the governor to commute Willie’s sentence. Governor Jimmy Davis, the country singer/writer of “You are My Sunshine refused and Willie Francis went to his fate on May 9,1947.

Willie Francis

Edward Honeycutt had escaped a lynching with cunning and daring. These personal qualities were useless in a jury trial for a black man alleged to have committed a felony against a white person in 1949 Louisiana. His destiny was probably already inextricably strapped to Gruesome Gertie. The trial did not go well. One of his lawyers and the prosecutor were brothers. His father did not testify because of the threats of violence against him. In fact, no witnesses were called by the defense.

The jury was all white. One juror had expressed an opinion regarding Honeycutt’s culpability and still was selected. Everybody knew the game was fixed. Honeycutt was found guilty and sentenced to death. The saving grace was that he recanted his confession. He described the beatings used to coerce the confession in detail. The prosecution did not counter with a substantial enough rebuttal. The defense files an appeal and on January 9, 1950 the Louisiana Supreme Court ordered a new trial for Edward Honeycutt.

Honeycutt & his black attorney (left) in court

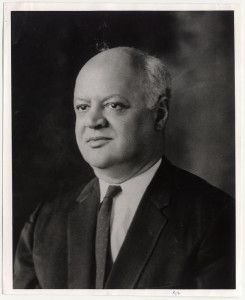

Union Parish supporters of the Honeycutt family travelled to Natchitoches, home of Dr. E. A. Johnson, president of the NAACP State Conference of Branches. They begged him to get the NAACP involved in Honeycutt’s case. Dr. Johnson appointed Louis Berry, Edward Jackson and Vanue LaCour to provide the defense in Honeycutt’s second trial. They were the first black lawyers to ever participate in a St Landry Parish criminal court. The environment was so explosive that Governor Earl Long provided protection for the lawyers on their route from Baton Rouge to Opelousas. Honeycutt faced another all-white jury. The black lawyers knew they had absolutely no chance of an acquittal. Therefore, they concentrated on shining a focused light on the selection process that resulted in the all-white jury.

One jury commissioner admitted that he did not submit the names of any blacks for the jury pool. Others spoke of the qualifications of blacks versus whites based upon their racist views of intelligence. As expected, Edward Honeycutt was found guilty and sentenced to death once again. The black lawyers appealed. The appealed failed. Gruesome Gertie was used to execute Edward Honeycutt on Friday June 8, 1951, exactly one week after my 5th birthday. Hundreds of white men and women gathered in and near the court house square to celebrate. It began a “Laissez les bons temps rouler” weekend.

Governor Earl K. Long of Louisiana

The guilty verdict in the Honeycutt trial proved to be a pyrrhic victory for the white citizens of St Landry Parish. A surprising transformation of the black citizenry occurred during the period just before the Honeycutt trials, appeals and the immediate aftermath. Returning black WWII veterans spurred on the fight for voting rights in most parishes. This was not true in St. Landry Parish. The few attempts to register for the 1946 and 1948 elections were turned back by intimidating threats and violence.

In June 1949, A. P. Tureaud, the great New Orleans civil rights attorney, filed a suit with NAACP support against the St Landry Parish school board on behalf of three plaintiffs. Pressure was immediately applied. One of the plaintiffs, Louis Thierry, owned a night club. He was arrested for allowing gambling within his establishment. His black cellmates brutally beat him. He signed a document repudiating the lawsuit. The other plaintiffs also withdrew.

Alvin Jones spoke at a civil rights rally in St Landry Parish sponsored by the Louisiana Progressive Voters League on Sunday June 4, 1950. Jones was the principal of South Town High School in Houma and former executive director of the New Orleans Urban League. The next morning, Jones led a group of 5 men to register to vote at the Opelousas courthouse. They were immediately attacked by a white mob and severely beaten with fists, brass knuckles and black jacks. Alvin Jones never recovered from his injuries. He died on October 31, 1951 at age 51.

The second Honeycutt trial was the catalyst for the metamorphosis within the black community. The segregated gallery and halls of the courthouse overflowed with over 1,000 black citizens. They were transfixed by Honeycutt’s team of black lawyers questioning pillars of the white community. The answers revealed the legally indefensible underbelly of their racism. Things would never be the same again.

St. Landry Courthouse

Richard Millspaugh, a 26 year old black Opelousas attorney, led a group of 15 men to the registrar’s office in October 1951. There was no white mob this time. There was not even a registrar present. Millspaugh quickly put a notice in the newspaper reminding the registrar of his duties. Vanue LaCour filed a lawsuit against the registrar on behalf of 3 of the men. One of the plaintiffs was 33 year old John Lester Mitchell, a WWII veteran and insurance agent. On Sunday morning November 18, 1951, the week before he was to appear in court for the lawsuit, Lester was shot and killed by a white deputy sheriff. The two other plaintiffs fled to Baton Rouge for safety. The suit was not dropped, but it never reached conclusion.

The parish had used up all of its chips with the US Department of Justice. Constant badgering from Tureaud shamed the Department of Justice into allocating assets to monitor the situation in St Landry Parish. The FBI had been involved in the Alvin Jones assault, although no indictments were issued. Parish authorities became weary opposing the Federal government. They called Richard Millspaugh in October 1952 and informed him that blacks would be allowed to vote. By 1956, 80% of the eligible black population in St Landry Parish was registered to vote. The racist temple that sacrificed Edward Honeycutt on the altar of injustice called Gruesome Gertie had not been torn down. But it was shaken to its foundation.

Attorney A. P. Tureaud

The arc of Edward Honeycutt’s story almost came full circle in a personal way during the summer of 1964. I had just graduated from high school. Our pastor had hired me to refurbish the pews in the church. I had been accepted into Xavier and it was his way of providing an opportunity for me to earn money to defray college expenses. I was walking home after work on this particular Friday afternoon. My friend, Ollie, pulled up beside me in his father’s car. He asked if I wanted a ride home. Ollie, although no angel, was for me like the River Phoenix character in the movie “Stand By Me”. He possessed an incredibly generous spirit. He was wise and perceptive beyond his years. During one period of high school, he noticed that I had developed an anti-authority faux tough attitude in order to be accepted by the rest of guys. He advised me that my ticket out was academics and I should not do anything to jeopardize that. He said that I was admired and respected for just being myself.

We were high spirited teen boys so, of course, we did not go directly to my house. We stopped at a liquor store and bought some beer. Then we started to cruise through the streets of Opelousas on that beautiful sunny afternoon. We were thinking that this was the prelude to a wonderful weekend. Eventually, we saw a car in front of us running a stop sign and hitting another vehicle. We did not stop to give witness because of the beer in the car. Frightened, we sped off and threw the remaining beer into a dumpster. The cruising continued. About a half hour later we were stopped by a couple of policemen. They asked us to follow them to the station. A white girl was apparently driving the car that ran the stop sign. The officers did not offer any details. It was all insinuations.

They were trying to frighten us into filling information unto a blank slate. We surmised that the white girl said we were following her and that she ran the stop sign in panic. They were ready to pounce on any hint of self-incrimination. Suddenly, Ollie’s poise asserted control of the interview. He said that we did not stop because we did not have time to give witness. He had to return the car to his father. He told them that we were good students headed to college in the fall. He reminded them that he was once a member of the Jr Police organization that their department sponsored. We had our whole lives in front of us. Why would we do what they were insinuating!

The officer in charge rubbed his chin and said that he was going to let us go. He warned that we had better not ever even think about doing what was being implied. He would contact us if there was a reason for another interview. We did not tell our parents about this incident. We lived in fear through the rest of the summer. I did not feel safe until I boarded the Greyhound to New Orleans. I don’t know why they let us go. It probably helped that we were unbearably clean cut with spotless records. I like to think that it was the force of Ollie’s eloquence. Over the years, his fluency during that interview has become as graceful and elegant as Honeycutt’s mythical dive off the Atchafalaya Bridge. I still remember Honeycutt every time I cross the bridge. Now I imagine there are three divers in the distant view of time. Honeycutt’s dive is in perfect shadow. Ollie and I are partially illuminated by the moonlight. Hands and feet pointed, we enter the water awake. We make it safely across the river. We, Ollie and I, gain the first light of big day and disappear into the canebrake.

canebrake

Irony of ironies, Ollie became an Opelousas policeman after USMC service in Vietnam. But, similar to the Chris Chambers character in “Stand By Me”, Ollie died young. He perished in an automobile accident at age 35. As for me, I vowed to never give the law an excuse to stop me. And, by chance, if I am stopped, I will be politely fearless. I am lifted up on the shoulders of our greatest generation.

James Guidry

Captivating story of a young man’s coming of age experiences, at the intersection of racial injustice and our ancestral history.

Wow! I grew up knowing all about the Honeycutt case. I personally knew Louie. Berry who was a law school classmate of my dad and practiced law in Alexandria, Law. At one point he even joined the faculty at Southern University Law Center where my dad had his life long carrier. I also knew Richard Milspaugh of Opelousas who had a strong association with my dad and their work with civil rights and voter registration

I am Vanue B Lacour Jr, the oldest child of my dad.

Simply awesome!

Look me up!

I am a great-great nephew of Louis Andre Martinet & a great-nephew of Hippolyte Martinet.

702-533-8908

Very informative and beautifully written.

These stories made heroes’ triumphs and tragedies come alive. Excellent writing!

Very thought provoking.

I look forward to James’ essay as they so eloquently capture the emotions and times that prevailed in Louisiana during those years. Unfortunately we must remain vigilant today as the doors of racial recriminations have been reopened. Thanks again for your insightfully inspiring reminders of just what is meant by “Take our country back.”

The doors were never closed! If we keep thinking it stopped, then we have a real problem. Lynching has taken on a new form which is police brutality, and some actually noose. Lynching is still happening. We are being murdered in public, on camera, yet no justice.

Great article James.

Excellent story that captures our historical, cultural and ancestral life in Louisiana. I’m a graduate student of Walter L. Cohen, Class of 1960.

So beautifully written. The imagery and voice are breathtaking . Mr. Guidry thank you for reminding me that there are many stories of the struggles of our ancestors which have not been told or written. Those of us who write, let’s get busy .

Well told! Thanks for sharing

Another great one dad. Hearing your stories and experiences growing up in the deep south during those tumultuous times is always interesting. Though it happened many years ago, the details are haunting and still relevant.

I have letters Honeycutt wrote to his family and were not passed on to them.

I would like To give them to his family.

Can your father help me locate them?

Frank, I will get in touch with Mr. Guidry and make sure that he receives your message. If Mr. Guidry is not sure of how to reach Mr. Honeycutt’s family, we at CreoleGen (as researchers) will be more than happy to attempt to do so. Thank you for getting in touch with us….Lolita

Thanks

My email is ffonzi@hotmail.com

Thank you. Your story and these men will stay in my mind and heart. This account of injustice is important. It must be hard to dredge up the fear and anger those times summon for you, but keep remembering and writing when you can James. Tell the stories and give these people honor and the times some sunlight.

James, AWESOME article. During the 50s and 60s, I remember hearing and reading about events such as you describe. As a young white man, I was horrified by the injustice.

James, you have a real talent for storytelling. I look forward to your next story. Please, keep them coming.

V/R, Bob Grenier.

THESE STORIES WERE VERY SAD, BECAUSE THEY WERE TRUE AND HAPPENED IN MY HOIME STATE OF LOUISIANA. I THANK JAMES FOR HIS COMPASSIONATE DETAILS OF THESE VICTIMS’ FATES.

Venue LaCour was my third cousin and I never heard this story til now. Thank you James!

Breathtaking. Thank you for opening the grave. These stories need to be told. It is so eloquently written. Again, thank you James for writing and CreoleGen for sharing.

JAMES, YOUR WRITING OF THIS INCIDENT(S) IS VERY MOVING TO ME….BORN AND RAISED IN SHREVEPORT, MY DAD HAD TOLD US ABOUT HIS FRIEND WHO HAD BEEN BEATEN TO DEATH IN JAIL FOR AN OFFENSE HE DID NOT COMMIT. SO MANY OF US HAVE STORIES LIKE THAT TO SHARE,; BUT, YOU DID A MARVELOUS JOB! ATTY. LACOUR COMES FROM CANE RIVER WHERE MY PARENTS ARE FROM.

KEEP WRITING!

A story told in such a way that the reader cannot escape it’s truth. I cannot think of any account that has moved me more. Let this be the beginning of a conversation that is as much needed now as ever it was.

Thank you for blessing these heroes with your narrative.

Thank you for this incredible story. My family on my Father’s side is from Opelousas and I never heard these kind of things spoken from them as a child visiting. I know from research that Louisiana had a history of lynchings and racism but your writing gives a voice to those unfortunate souls who were the victims of these injustices.

Thank You.

Beautifully written. Keep it coming James

James, we spent four years at Xavier together and not once was I aware of your experiences that formed the foundation of the student I knew back then. Hope we get a chance to reconnect at our Class of ’69 50th Reunion this Fall.

The Honeycutt murder happened the Thursdays before my parent’s wedding. My mother would tell me of this when I left for Grambling State University as she armed with the speech that every black gets when going away from home. The fear was discernible in 1990 and even today, in 2024. I pray that Honeycutt’s life continues to remind us to understand why it is important.

Thank you for your comments. The Honeycutt trial galvanized the black citizens of Opelousas. It will be the 73rd anniversary of his execution on June 8, one week after my 78th birthday.

Well told, James. I had not heard these stories but did hear others from my dad based on his own personal experiences. Such a sad history, but it certainly left its mark on several generations.

There are many untold real life experiences like this one, endured by Black Americans both in cities large and small. Thank you for being brave and standing up to the lies of those trained to lie and “just blame it on the nigger” without ANY conscience whatsoever.

Beautiful telling of a horrific story.