The successful strivings of Negroes for enlightenment under most adverse circumstances read like beautiful romances of a people in an heroic age. – Carter G. Woodson.

In the epic saga of affording an education to blacks after the Civil War, there are not volumes enough to recount the lives and good works of those heroic men and women who traversed the South leading one-room shanty schools, building normal and religious institutes, and comprising the faculties of institutions of higher learning.

In New Orleans, there were four such early institutions – Straight University, New Orleans University, Southern University, and Leland University. Leland University, founded in 1870, occupied a beautiful Saint Charles Avenue campus from 1873 to 1915. Until the September 1915 Hurricane, Leland’s two imposing main buildings, Chamberlain Hall and University Hall, towered over the spacious and well-placed campus.

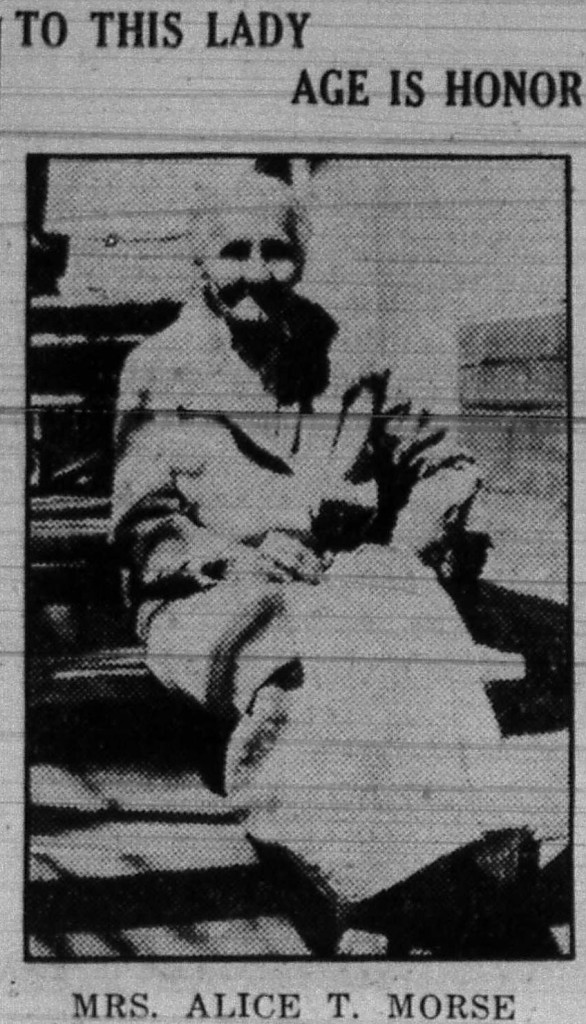

Chamberlain Hall, was home to the female dormitories, as well as many of the classes popular among young ladies. This was the domain of Mrs. Alice Thornton Morse, who was described as “one of the most illustrious women ever interested in the educational welfare of her people.” For thirty-five years, Mrs. Morse was engaged in the work of teaching at Leland University.

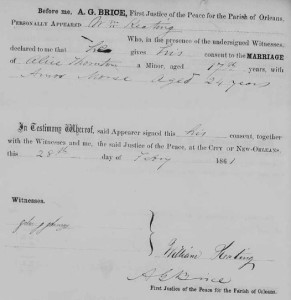

Mrs. Morse was born Alice Thornton in Mississippi about 1844. Though free prior to the Civil War, the circumstances surrounding her birth and free-status are as of yet unknown. In February 1861, at the young age of seventeen, she was married to Amos P. Morse, a literate free black man, who was then twenty-four years old. Amos Morse worked as a porter aboard the luxury steamers which went up and down the Mississippi River. Being a minor, her marriage was consented to by a William Keating, whose relationship to Alice is still unknown.

Over the twenty-five years of their marriage, Amos and Alice had eight children, the names of six of whom are known: Odalie, Adele, Amos Jr., Desiree, Wilhelmina, and Ethelene. Not long after the birth of her last child, approximately 1880, Mrs. Morse began her thirty-five years of service to Leland University. She taught sewing and served as house mother to hundreds of pupils under the administrations of five presidents at Leland. She remained at Leland until it was relocated to Baker, Louisiana in 1915.

Mrs. Morse was a well-educated woman, who participated in dramatic presentations at the Lyceum, alongside many of the city’s black socialites in the 1870s. In the May 1889 issue of The Baptist Home Mission Monthly, the corresponding secretary of the American Baptist Home Mission Society reported that the two colored faculty members at Leland, Mr. Jonas B. Henderson and Mrs. Morse, were “deservedly held in high esteem.”

Mrs. Morse’s role in teaching sewing and serving as prefect to Leland’s young ladies cannot be overstated. She equipped the young women with a skill which would allow them to make a living for themselves and their families. Her example, as a cultured, educated woman of color was important for so many young women who ventured from small preparatory academies across the state to Leland. Many of them were away from home and away from rural farm life for the first time.

Her husband, Amos P. Morse, died aboard the palatial steamer, J. M. White, which burned and sank at Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana on 13 December 1886. Mrs. Morse was left widowed with six children. Fortunately, one by one, her daughters, all alumnae of Leland, followed her into the teaching profession. They found appointments in schools in New Orleans and throughout rural Louisiana. Her only son, Amos Morse, Jr., worked as a plasterer throughout his short life. Amos Morse, Jr. (born 14 April 1866) died on 3 Nov 1904 at the age of thirty-eight. With his wife, the former Mary Cray, Amos had two children, Joseph Morse and Wilhelmina Morse.

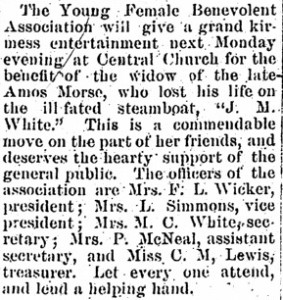

Mrs. Morse’s friends rallied to her aid following the her husband’s tragic death. In testament to the high esteem in which she was held, the Young Female Benevolent Association sponsored a grand fair for her benefit at Central Congregational Church in May 1887. The association was led by Mrs. Frances L. Wicker. Just prior to the turn of the century, Mrs. Morse moved to 7311 Burthe Street in the Carrollton section, where she lived until her death.

Her oldest daughter, Odalie Alice Morse (born 13 May 1865) taught briefly at Leland, like her mother. Odalie also served as the first Vice President of the Phyllis Wheatley Club, a colored women’s club much concerned with social and educational uplift and women’s suffrage. On 15 June 1893, she married the Reverend Andrew Stephen Jackson, who was a member of the Board of Directors at Leland and for eighteen years, pastored the Tulane Avenue Baptist Church. Together, Odalie and her husband had two sons, Alexander Hubert Jackson and Maynard Holbrook Jackson, before moving to Dallas, Texas in 1899. Mrs. Odalie Alice Morse Jackson and the Reverend Andrew Stephen Jackson are the grandparents of the Honorable Maynard Holbrook Jackson, Jr., who became the first African-American mayor of Atlanta. Odalie Morse Jackson died in Dallas on 7 June 1941.

The second eldest child, Adele Morse (born 8 January 1867) was married to Frank Paul Martinez, a brick mason, on 4 March 1889. They had two children, Frank Paul Martinez, Jr. and Adele Maria Martinez (Mrs. William E.) Stewart, who were both reared by their maternal grandmother. Adele Morse Martinez died as a result of childbirth on 8 August 1891.

The third daughter, Desiree M. Morse, was married to Alfred C. Priestley, Sr. Priestley, a native of Saint James Parish, was like his bride, a Leland alumnus and an educator. The Priestleys had one daughter and four sons, including legendary Xavier Coach Alfred C. Priestley, Jr. Mrs. Desiree Morse Priestley died on 29 June 1960.

Wilhelmina Corona Morse taught school in southwest Louisiana and ultimately married Dr. Walter Henderson Ennis, a physician. They settled in Crowley, Louisiana, where Wilhelmina taught for several decades. She died in Crowley on 21 September 1961.

Ethelene Morse, the youngest child, married Dr. Alexander H. Brown, a physician, and made her home in Little Rock, Arkansas, where she taught for several decades. Her daughter, Alice L. Brown, later followed her into that profession.

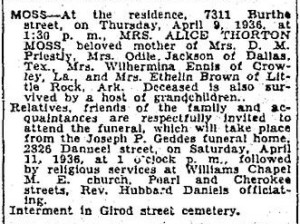

When The Louisiana Weekly profiled Mrs. Alice Thornton Morse in November 1931, the article’s title read “To This Lady, Age is Honor.” To have reached her then eighties and having had the comfort of serving as a teacher and guide to so many young women who attended Leland University was indeed a great honor. Moreover, that Mrs. Morse lived to see her children and grandchildren carry on her legacy in teaching is remarkable. Living as free prior to the Emancipation Proclamation, classed Mrs. Morse with less than ten percent of all people of color in the country in 1860. Her early education put her in a position to exemplify noblesse oblige – that to whom much is given, much is required. Even then, in 1931, approaching her ninetieth birthday, Mrs. Morse’s greatest wish was to see her beloved Leland returned to New Orleans. On 9 April 1936, at approximately ninety-two years old, Mrs. Alice Thornton Morse passed away after a long and productive life. She was buried from the Williams Chapel Methodist Church and was interred in the long-since gone Girod Street Cemetery.

Teaching is a very noble profession that shapes the character, caliber, and future of an individual. If the people remember me as a good teacher, that will be the biggest honor for me. – P. J. Abdul-Kalam.

Jari Honora

Sources: New Orleans Justice of the Peace Marriages, Amos Keating and Alice Thornton, 28 Feb 1861, microfilm roll VEB-678, pages 227-228; “Concert And Exhibition,” Weekly Louisianian, 17 March 1872, page 2; “Notes of a Southern Tour,” The Baptist Home Mission Monthly, Vol. 10: No. 5, page 110-111; The Times-Picayune, 11 April 1936, page 2; The Weekly Pelican, 30 April 1887, page 3; The Louisiana Weekly, 14 November 1936, page 5; University of Louisville Digital Collections, Howard Steamboat Museum Collection, http://digital.library.louisville.edu/cdm/landingpage/collection/howard/.

My paternal aunt, Hilda Gardner Roy ’31’s Ronegale is somewhere here in storage and I will be looking for it soon. I took my aunt to her class luncheons and felt like a member of the class. Her classmate Mr. Maye was my 3rd grade teacher at Mc#37. My maternal uncle Alvin Turner is in the pictures of the sports teams. I enjoyed reading about Leland which my freshman high school teacher, Ms Helen Toliver BTW, spoke about often. I truly enjoy your research. Please continue!!

Hi Ruth !! This is a wonderful place to find …distant friends ,isn’t it? I really miss not being w/ my “Gene” friends and acquaintances!

Ms. Helen Toliver was a friend of my family !! I also have kept my mother’s certificates ( a McDonogh Elementary/1919, McD # 35 High School/June 7,1923, New Orleans University/May 24,1928 . Are you on FB ??