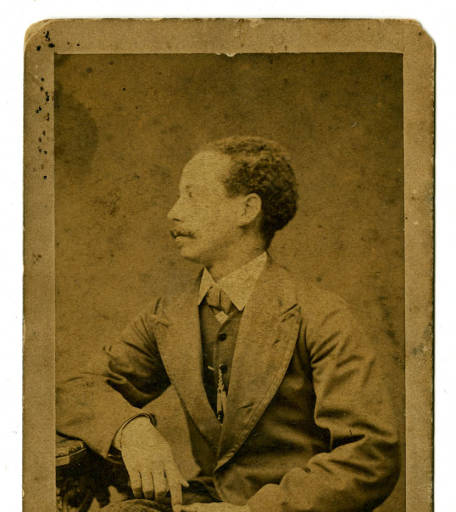

Basile Jean Bares (1845-1902)

{Cabinet Card Photograph taken 1870 in Paris, France}

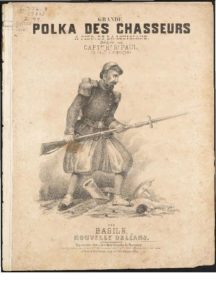

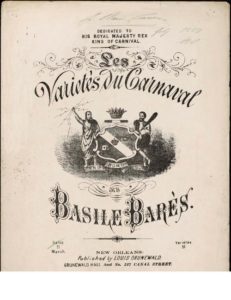

Inside the lobby of the historic Roosevelt Hotel can be found a baby grand piano that once belonged to one of the most popular pianist and composer of dance music in New Orleans following the Civil War. His name at birth was simply “Basile” but he would, by the age of 16, compose, publish, and eventually copyright his own piece of sheet music. What makes this music so unusual is that it was the work of a slave, published while he was still a slave. The year was 1860 and the work was entitled, “Grande Polka des Chasseurs a Pied de la Louisiane.”

Who was this slave child and how could this have been? Basile and his younger brother, Adrien were born into the household of Adolph Perier, their slave owner. “Augustine” (their mother) was also the property of Mr. Perier. Perier had purchased her from Felicite-Amynthe Bienvenu, who received Augustine in a divorce settlement from her first husband, Nicolas-Theodule Delahoussaye.

Baptismal record for Basile, (dated February 9,1848, one exact month after his birth) was discovered in St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church in the French Quarter. No father or godmother was listed, only his mother and a white godfather named “Jean”.

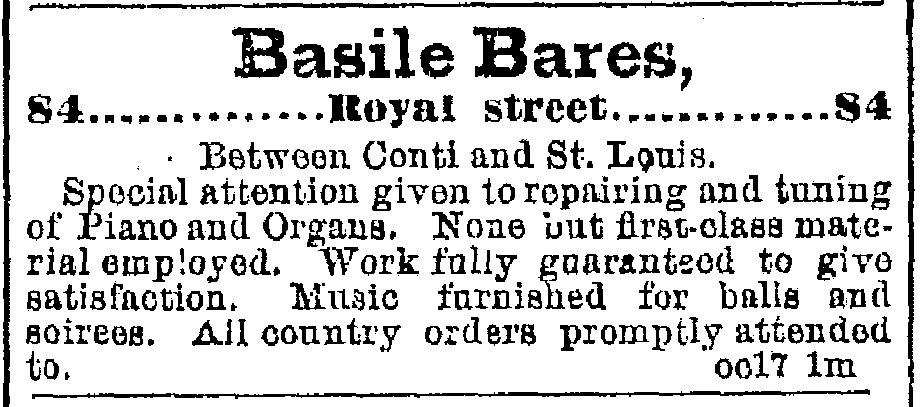

Adolph Perier and his wife were the proprietor of the Perier Piano and Music Emporium on Royal Street between Conti and St Louis. Visitors to the music store often noticed a young boy and his younger brother working there, learning how to repair and tune pianos and organs while also learning how to play them. Visitors often referred to the older of the two as “Basile Perier”, believing he was Adolph Perier’s free, mixed race son; but this would later be proven to be untrue.

Basile and Adrien’s upbringings in a piano store took place during the era in New Orleans when sheet music was extremely popular. From the 1840s through the early 1900s, this form of music consisted almost entirely of songs with piano accompaniment, dances for pianos and piano scores of marches.

It was also the period when such New Orleans musical figures as: Edmond Dede, Eugene Victor Macarty and Lucien Lambert (all born free) began composing music that enabled them to become well known here and in France. So, it is surprising that Basile, enslaved, could become a great pianist and possibly begin composing dance music of his own.

Basile would eventually study piano under Edmond Dede’s old hometown teacher Eugene Prevost and composition plus harmony under C.A. Predigam.

After the Civil War, Basile traveled several times to Paris on business for the Perier firm and performed at the Paris World Exposition of 1867 for four months. He may also have gained further musical training while in Europe. After Adolph Perier’s death in 1860, widow Charlotte Perier kept the music store and Basile, as well as his brother Adrien, continued to work there.

The surname “Perier” stuck with Basile throughout his younger years. Marcus Christian often noted that even the black-owned newspaper, New Orleans Tribune often referred to the young pianist in the mid-1860s as “Basile Perier.” But by 1865, Basile’s stage name “Perier” disappeared from newspaper records and was replaced by “Bares.”

The surname “Perier” stuck with Basile throughout his younger years. Marcus Christian often noted that even the black-owned newspaper, New Orleans Tribune often referred to the young pianist in the mid-1860s as “Basile Perier.” But by 1865, Basile’s stage name “Perier” disappeared from newspaper records and was replaced by “Bares.”

As with so many enslaved people, Basile was not allowed to freely use his father’s surname “Bares” until after Emancipation. Now his true identity could be known. His father was Jean Bares, a white French carpenter who immigrated to the city in 1838 and became a grocer. Jean Bares, Basile’s godfather, was listed only as “Jean” on his Catholic baptismal certificate. This was a common practice used by many white fathers upon the birth of their enslaved mixed-race children. Basile and Adrien Bares were always aware of their father’s true identity and indicated so on marriage and death records.

In 1877, Basile Jean Bares married Leontine Araiza and together they had eight children. They were: Basile Jr. (1871-1873); George (1873-1873)); Lucie (1874-1941); Basile Eugene (1876-1912); Marie Augustine (1878-1936); Ernestine Leontine (1879-1962); Louis Victor (1881-1882); Basile J. Maxine (1882-1899). From 1871 through 1897, the Bares family resided at three locations; 232 Royal, 323 Bourbon, and 618 Barracks streets.

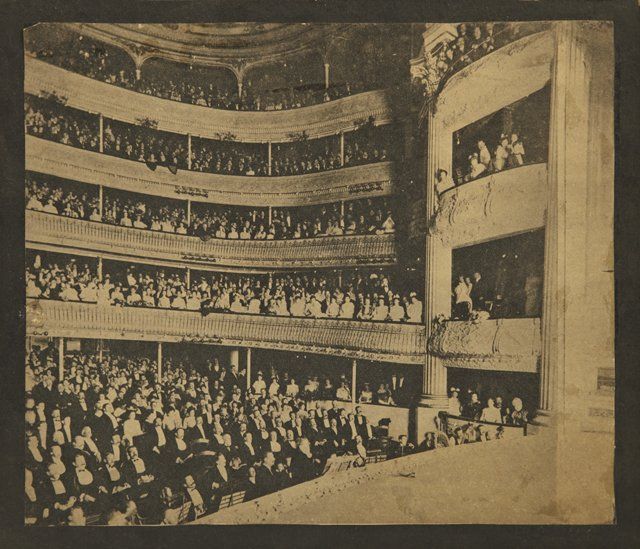

In the 1870s, Eugene Macarty, Basile Bares, and Samuel Snaer (three composers of color) began to organize concerts aimed at audiences of Creoles of color. Bares became involved in the issue of segregation at the French Opera in the 1874-75 season. Once Union soldiers left the city after Reconstruction, management of the opera house tried to retreat back to enforcing separate seating of the races. As a result, Creoles of color staged a boycott which caused the opera house to fail to pay its singers at the end of the season. In town were foreign singers who, without being paid, could not return home to France. Basile performed a benefit for the singers before a large black audience. It was successful and the singers were able to return to France.

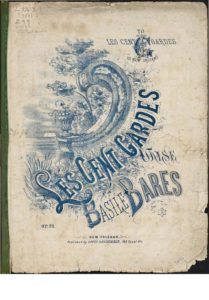

In the next two decades (1870-1880s) Basile Jean Bares developed a large public following of admirers. Between 1860 and the late 1880s, he published nineteen of his dances for the piano. He also led a popular string band that performed at many local white carnival balls.

Most of Basile’s music copyrighted in the 1870s was published by Louis Grunewald whose music store Bares worked at for a large portion of the decade. In the 1880s, he worked at the store of Junius Hart, who also published some of the pianist’s works.

Most of Basile’s music copyrighted in the 1870s was published by Louis Grunewald whose music store Bares worked at for a large portion of the decade. In the 1880s, he worked at the store of Junius Hart, who also published some of the pianist’s works.

From the latter 1880s (while still in his early 40s, and until his death in 1902), no further works by Basile seem to have been published. All of Basile’s children learned to play the piano. Lucie and Basil Eugene became piano teachers and they all seemed to know how to repair and tune the instruments.

Unfortunately, there are no known direct descendants of Basile Bares alive today. Fortunately, the legend of the talented slave boy can be told through those descended from Adrien Bares, Basile’s only sibling.

Adrien also became a pianist, married Emily Concage and brought three children into the world. One of whom was Mary Augustine Bares who would marry in 1889, a local insurance agent named George Godfrey.

My mother never knew this but she and her siblings: (Blanche, Dorothy, George Albert, Frances, Emile, Lillian, Emanuel & Emily Godfrey) are the great-grandchildren of Adrien Bares. Therefore, Basile Bares is their great-grand uncle.

Now I know why my mom always loved piano music.

Sources: Succession of Adolph Perier #88478, (1860) Orleans Parish Civil District Court; Creole: The History and Legacy of Louisiana Free People of Color, edited by Sybil Kein, LSU Press, Chapter 4 “Composers of Color of 19th Century New Orleans, written by Lester Sullivan, pages 71-96; Music of Basil Bares (Compact Disc) played by Peter Collins, Centaur Records; New Orleans Archdiocesan Archives, Baptism of the slave Jean, Book #2 (1844-1867) p.10, Act 58 , St. Mary’s Catholic Church; Ancestry.com (various federal censuses 1870-1910) ; Louisiana State Archives (births, marriages, deaths records) and www.sos.la.gov . Xavier University Archives (Basile Bares’ Photo) & Jari Honore for his research assistance.

Lolita Villavasso Cherrie

This is a great article. OperaCréole is proud to present Basile Bares’ music and him as a singing character in our newly created opera “The Lions of Reconstruction” next weekend.

Thanks for the wonderful information.

Hi I found out I’m Basil’s Bares great Granddaughter. I had results from ancestors.com. I found this amazing. I’m probably the only living relative now. Just thought I’d let you know.

Hi Deborah,

I am the great-great granddaughter of Adrien Bares, Basile Bares’ brother. Let’s communicate. I have sent you a personal email. (Lolita)

This is how our history and heritage has been kept away from us. Keep on educating us who work to educate the next generation.

thanks

Living in those constraints, of the times, they lived; proves once again, you can’t imprison spirit, or talent. It’s like the air you breathe. An inspiring true story, not lost to time.

Merci Beaucoup for publishing Monsieur Barre. We all shall benefit from our history.

Very interesting story. Thank you!

Thanks to Lolita Villavasso Cherrie for this EXCELLENT piece! I encourage everyone to witness Bares come to life in OperaCréole’s “Les Lions of Reconstruction.”

Bravo! Thank you for always uncovering and deciphering these hidden histories of our people. Creolegen is one of a kind and exemplary at what you do! xoxo Dianne Gumbo Marie Honore

Awesome story! Thanks for sharing.

This was a great read. Thanks

Wow what a great piece of information you found. Is he in anyway related to my grandmother Viola Coustant?

Bravo Lolita,

you come from very accomplished people! But that is no surprise. Keep up the good work and continue to educate us!

Gregory Osborn

I am a musician. I play guitar. This is amazing to find an ancestor of mine who was also a

musician.

What an exciting find, cousin. Great family history to share.

Thanks! Ms Cherrie, continue your marvelous research. There has been several people and places in your research which brings back memories fopr me. Having given guided tours in the James Gallier, Jr. townhouse in the 1100 block of Royal St., I am sad the beautiful French Opera House he built was not restored.

Thank you for this interesting information. I love finding these little musical gems of New Orleans. Stumbled across his piano at the Roosevelt Hotel in New Orleans and just had to know all I could.

A well Incredible story that depicts a lifestyle from the past where the African American was once again able to endure and prevail through will and determination. The youth must be taught about its roots.

What a great story, and how inspiring!