It is nearly impossible to find a New Orleanian or anyone in the sugar-growing parishes of Louisiana who does not instantly recognize the name Godchaux. Whether they shopped in the family’s flagship Canal Street department store, or remember the town of Reserve when it was a virtual company-town for Godchaux Sugars, or were associated with one of the many sugar plantations the family operated after the Civil War, it is hard to not find some connection to the dynasty begun by Alsatian Jewish immigrant Leon Godchaux in the 1840s.

Leon Godchaux – Source: Godchaux-Reserve Historical Society (godchauxhouse.com)

The oft-repeated story is that Leon Godchaux arrived in New Orleans in 1840 in his late teens and with a determination to gain success in business. Joachim Tassin, described in various accounts as an octoroon, free man of color, and speaker of five languages, was purportedly, either a native of New Orleans or a Jamaican, who was a member of the crew of the ship upon which Godchaux arrived. The two young men befriended each other and became a “two-man store on legs,” carrying their peddlers’ packs up and down the River Road calling on plantations and small farmers. They established a small permanent store at Convent in Saint James Parish, before Leon Godchaux ultimately decided to enter business in New Orleans.

Another claim that has been made time and again by historians and descendants of Leon Godchaux is that he never owned slaves. In actuality, the association between Joachim Tassin and Leon Godchaux both belies the legend surrounding their relationship and the assertion that Godchaux was not a slaveowner.

On 3 October 1849, notices were posted in French and English throughout Saint John the Baptist Parish – on the door of the courthouse, the parish church, Fortineau’s store, and Savoie’s billiard hall – that on 3 November, a month later, the property and effects of the late Jean-Baptiste and Clarisse Tassin would be sold at auction to settle their estate. Among the bidders that day was Leon Godchaux, who had been a Southerner-by-adoption less than a decade, and his older brother, Mayer Godchaux. The Godchaux frères, as they were styled, became the owners of a seventeen-year-old enslaved mulatto créole named Joachim, whom they acquired for seventeen hundred dollars. These ambitious young men made their purchase entirely on credit, with three equal notes backed by Jean Hahn, with whom Leon had executed a business partnership in 1847.

For the next six decades until his death in 1910, Joachim Tassin would remain connected to Leon Godchaux and his clothing business. In those early years, the world of the Louisiana Creoles was somewhat insular and the presence of Tassin, standing at about 5’7, with hazel eyes and yellow complexion, and speaking with the familiar dialect heard along the River, would have made a helpful companion to Godchaux as he did business between New Orleans and Donaldsonville. The sugar-growing region along the River Road was the only world young Joachim had known. He was baptized when he was six months on 18 August 1832. He was born to Thérèse, an enslaved woman owned by Jean-Baptiste Tassin.

By 1845, Godchaux had begun his store in New Orleans on Old Levee (Decatur) Street. In this new permanent venture, the staff was enlarged to include Rosemond Champagne, who like Tassin was a native of the River Parishes; and Charles Steidinger, who started with Godchaux when he was just a boy. The business continued successfully amid the changing political, social, and economic climate. At the end of the Civil War, Leon Godchaux purchased property in the 500 block of Canal Street at the corner of Chartres, where by 1876, he had completely moved the business. Through all of these changes, Joachim Tassin remained an ever-constant presence at Godchaux’s.

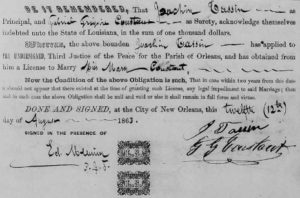

The War brought about changes for Tassin as well. In the spring of 1861, following the start of the Civil War, Tassin like hundreds of other men of color in and around New Orleans enlisted in the First Louisiana Native Guard, a Confederate militia regiment which disbanded when the city fell to Union forces the following year. On 12 August 1863, he married the sister of one of his fellow soldiers and St. John Parish natives, Gabriel-Gregoire Coustaut. Joachim Tassin and Marie-Madeleine-Elene Coustaut were married at Saint Augustine’s Church. Tassin and his new bride resided in the home he purchased in 1865 at what is now 1031-33 St. Ann Street (then 157 St. Ann). They lived on St. Ann Street until 1880, when they moved to Decatur Street. Joachim Tassin and his brother-in-law G. G. Coustaut were also among the more than eight hundred men of color who signed an 1864 petition to President Abraham Lincoln demanding the right to vote.

Marriage Bond (1863) – Joachim Tassin and Marie-Madeleine-Elene Coustaut

For approximately eight years, from 1876 until a disastrous fire in August 1885, Tassin left Godchaux’s and operated his own clothing store. The store was first located at the present 933 Decatur Street (then 241 Decatur). From 1881-1885, the store was located at what is currently 819 Decatur Street (then 205 Decatur), just across the street from the famed Madame Begué’s Restaurant. A year prior to the fire, Mrs. Tassin died of uterine cancer in her early forties on 18 April 1884.

View of Decatur Street including J. Tassin Clothing Store -Source: Louisiana State Museum

Advertisement for J. Tassin Clothing Store – 1876

Following the death of his wife and the fire which destroyed his entire inventory, Tassin returned to Godchaux’s, with which he had been associated since 1849. He also moved out of the French Quarter to 1471 North Roman Street, where he resided for the rest of his life. Reflecting on his importance and longevity of service to the Godchaux clothing store, The Daily Picayune stated in 1910:

“Four generations of New Orleans citizen and citizens-to-be have had their clothes fitted to them by Tassin. It was no unusual thing for aged men to bring in little tots to have their first trousers put on by Tassin, who have done the same for their grandfathers. There are many accounts on the Godchaux books today that were first brought in by Tassin when the store first opened and have been kept there since; accounts passing through three generations. The only vacation Tassin ever took was a trip to Europe. He toured the old world for six months. His other absence from continuous employment with the Godchauxs [was] the eight years he ran a store of his own at Jefferson Street and the riverfront. When he sold out, he secured a good price for his large trade with West Indian shipping. He spoke English, French, German, Italian, and Spanish. Whenever any doubt arose on a business matter, if Mr. Godchaux was not about, Tassin would be consulted by other employees and the difficulty was over.”

Godchaux Building at Canal and Chartres Streets – 1899

When Leon Godchaux was laid to rest on 20 May 1899, his former slave and first employee, Joachim Tassin, was there and was named an honorary pallbearer. He never lived to see the opening of the magnificent six-story “skyscraper” Godchaux Building at Canal and Chartres, but the ever-dutiful Tassin did. Joachim Tassin remained actively engaged in the store until two years before his death, when he was pensioned by the firm. Even afterwards, he would frequently return to visit the site of his labors for most all of sixty years.

At some point between the death of his wife and the early 1890s, Joachim Tassin began a relationship with a native of Bordeaux named Marie-Pauline Millon. Joachim Tassin died at approximately eighty-two years of age on 2 May 1910. Two days later, on 4 May 1910, he was buried from his home at 1471 North Roman Street and interred in the beautiful tomb he owned in Square 2 of Saint Louis Cemetery No. 2. His estate consisted of his tomb and three pieces of property. With the exception of a few cash bequests, the entirety of his estate was left to Pauline Millon, who survived him by twenty years.

Tomb of Joachim Tassin in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2, Square 2

Tassin’s story underscores the complexities of master-slave relationships; the history of the sizable but not well-known Alsatian Jewish migration to the South; and the success of two industrious men – Leon Godchaux and Joachim Tassin.

Sources: Item, October 17, 1910, page 20; Times-Picayune, March 1, 1940, page 42; March 1, 1940, Page 41; May 3, 1942 page 85; January 25, 1937 page 246; Daily Picayune, May 4, 1910 page 5; August 3, 1885 page 1; May 19, 1899, page 3; Succession of Joachim Tassin, Docket No. 93,452, Division B, Orleans Parish Civil District Court, New Orleans Public Library Louisiana Division; Passport Application for Jassin [Joassin] Tassin, 6 April 1896, No. 9083, National Archives and Records Administration, Microfilm Roll No. 462 (1 Apr 1896-13 Apr 1896); Sale of Slave – Succession of Jean-Baptiste and Clarisse Roussel Tassin to Leon and Mayer Godchaux, 30 November 1849, Notarial Acts of Charles Boudousquie, Volume No. 29, Act No. 275, Page 160, New Orleans Notarial Archives; Baptismal Register No. 8, Page 189, Saint John the Baptist Church, Edgard, Archdiocese of New Orleans Archives.

Jari Honora

Great read, about a very complicated relationship.

Thanks.

This is an amazing account (..with citations) of life in Louisiana at that time. Thank you.

Wow thanks for sharing this, I knew about Godchaux’ but nothing about Joachim Tassin.

I’m so delighted at this story; and yet, I’m crying. Thank you Jari. So beautiful, so glorious and tragic the drama of life. I will pay homage at his tomb.

Excellent!!

Thank you so much for this post…. I recognize the Tassin family name and could be related somewhere down the line….

My mother is a Tassin living in Calif. Her father was Farrell Tassin .

Was your father’s nickname Buchee, or something similar? If so we are related and I remember your family very well. They use to come visit us uptown on Liberty St.

I love this story

Joachim Tassin….would be in my tree..somewhere…..but where?……………………….

Another great story. Thank you for your research and sharing.

This story touches my heart because my mom is a Tassin & will be excited to learn about this history . Thank you so much

I appreciate all your research ’cause it increases my knowledge of my city and its people. When the Tassins were recognized at the Whitney Plantation Dedication, the name sounded familiar but I did not know the family history (I knew the Haydels: CC,Jr. my classmate and his mother my soror.) Thank you!! I look forward to more of your work.

I really enjoy all of the Creole stories of such great people.

Great story. I am a descendent of the Coustaut (Crusto) family. Blessings, Mitch