From New Orleans Public Library, Louisiana Division

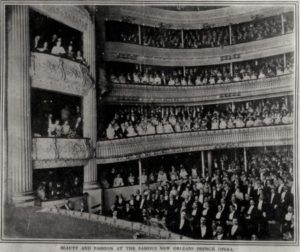

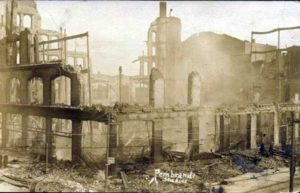

When a disastrous fire destroyed the French Opera House one hundred years ago on December 4, 1919, it was lamented not only as an icon of the city’s musical culture but as another death knell for its Créole population. For roughly three generations, the imposing Italianate structure at the uptown, lakeside corner of Bourbon and Toulouse streets had been a part of the physical cultural patrimony of the city’s old Francophone residents, both white and black.

In a recent article in the Picayune, Richard Campanella attributed the Opera House’s success in spite of war, epidemics, and upheaval to the “enthusiastic patronage of the [Creoles], both white and black.” Campanella further observed that, “Critical to their cohesion were keystone civic institutions, providing French Creoles with social space and cultural sustenance counteracting the forces of national assimilation. St. Louis Cathedral and other downtown Catholic churches, for example, bonded them religiously. About 20 tiny private academies – so-called ”French schools” taught by aging Creole society gentlemen [and women] like Alcée Fortier – kept alive their language and heritage. And the Old French Opera House kept them entertained through French themed performance arts.”

Title of article on Leontine Adonis Fernandez, 2 March 1919, The Times-Picayune

One aged Creole who witnessed the construction of the French Opera House and its fiery demise was Mrs. Léontine Adonis Fernandez, who lived at 2624 Hospital Street (now Governor Nicholls Street). A writer for the Sunday Times-Picayune profiled Madame Léontine just before she attended an afternoon performance of Faust and an evening production of Aïda on 2 March 1919.

Léontine Adonis was born in approximately 1847 in New Orleans and was married in about 1870 to a barber named Ernest Fernandez. Reflecting the Creoles’ interest in pedigree and history, she noted in her interview that she was a “real Créole,” born “down on Royale [and] remember when Opera House was built.” As the newspaperman noted, “her father came from Spain and her mother was a slave from Cuba. Both of them died of fever before the War and Léontine was brought up by Madame Capdevielle.” Léontine and Edgar Fernandez had six known children, not surprisingly the oldest of whom was given the literary-inspired name Roméo, within months of Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette being first produced in New Orleans at the Opera House.

Following the death of her husband on 13 June 1889, she provided for her surviving son and four daughters, by her work as a cook. At seventy-one years of age, Madame Léontine with her skin described as “café au lait,” had a spryness and agility that led her to effortlessly ascend to the poulailler (literally “chicken coop” or top level), where the laws of Jim Crow dictated she sit.

Despite her humble birth and the insulting limitations of segregation, she was praised as one “whose record for opera attendances places her among the music veterans of New Orleans. … She can criticize the production of an opera and praise or condemn a singer with what is said to be unerring judgment. … Called from a kitchen on Ursulines Avenue where she reigns supreme in a downtown household, Leontine will dissect an opera or place a singer with the utmost sangfroid.”

Giving the reader an indication of her tastes, the article reads: “Faust is well enough; Rigoletto – oh, pretty good; but Pagliacci, Mignon, and La Favorita are real operas. She saw Madame [Sarah] Bernhardt on her last visit here but prefers Theda Bara’s interpretation of Camille. Theda is her favorite screen actress, but she does not give the movies much praise, while the comedies she blast with her scorn as ‘foolishness.’”

From New Orleans Public Library, Louisiana Division

Having frequented the French Opera House for all of its sixty years of existence, one can only imagine the loss Léontine Adonis Fernandez felt some nine months after she was covered in the Picayune to awaken on December 4th and discover that this bastion of old Créole New Orleans had been destroyed.

Frank P. Farrell, another Créole of color and a civic and fraternal leader, shared in her sense of loss. As a side pursuit, Farrell worked for many years in the cloakroom of the Opera House and saw many of its splendid Carnival pageants. He lamented in a letter-to-the-editor two years after the devastating fire that as the Carnival season approached (in January 1921), that there was nothing to indicate to the throngs of visitors where the venerable old building once stood: “[Some] display should cover the site, or a sign displayed pointing out to strangers the place where the French Opera stood before the fire. There seems to be a disposition on the part of some to set at naught things of a historical nature belonging to old New Orleans, and the desecration of the spot where the French Opera House stood seems to be in line with the new progress New Orleans is making in the downtown section of the city.”

Léontine Adonis Fernandez, the Créole cook and devotée of the French Opera, died on 22 May 1922 at approximately seventy-four years old. She was interred in Square 1 of the Saint Louis Cemetery No. 2. She was survived by her son, Edgard Fernandez, Jr., and her daughters, Ernestine Fernandez Perkins, Léontine Fernandez, Sophie Fernandez Dumas, and Virginia Fernandez Metoyer.

Jari C. Honora

Sources: 1880 Census, Orleans Parish, Louisiana, Roll: 461, Page: 211D, Enumeration District: 35; Edgar Fernandez household; 1920 Census, Orleans Parish, Louisiana, Roll: T625_620, Page: 7A, Enumeration District: 105, Joseph Jarde household; “Holder of Grand Opera Record Ready for Treat” The Times-Picayune, 2 March 1919, page 44; Léontine Fernandez death record, Orleans Parish Death Records; Louisiana State Archives, Volume: 184; Page: 753; Richard Campanella, The Times-Picayune, 1 December 2019. Pictures (except where noted) from: “Que la fête commence!

The French Influence on the Good Life in New Orleans” (Online exhibit), New Orleans Public Library, Louisiana Division, http://nutrias.org/exhibits/french/french.htm.

Such a wonderful story!!! It’s one thing to know our people were in the audience, but to read her reviews is priceless!!