One of our goals with CreoleGen is to shine a light on the parallel world which people of color were forced to build for themselves during the many decades of Jim Crow segregation. The business, civic, educational, social, and religious leaders created and sustained a myriad of businesses, institutions, and associations within a largely self-sustaining and self-governed community.

In October 1952, veteran educator and journalist Orlando Capitola Ward (O.C.W.) Taylor proposed to a group of business and civic leaders that they pool their resources to establish a country club for New Orleans’ Black community. They began a campaign to purchase the palatial River Bend estate of millionaire Blaise D’Antoni (President of Standard Fruit Company) located about a mile-and-a-half below Violet in Saint Bernard Parish. In addition to the two-story mansion, the 137-acre River Bend estate included several guest houses, a large barn, and an enclosed swimming pool.

River Bend Estate

Over the three months between October 1952 and January 1953, Taylor and his group attempted to raise the $25,000 necessary to meet the first two installments on the purchase of River Bend. The Crescent City Country Club investors developed plans to add approximately $150,000 in improvements to the site including a tennis court, golf course, and a dancing pavilion large enough to accommodate “1,000 couples.”

In early January, the club’s Board of Governors announced that they had begun raising funds and had formed six committees to assist with the club’s operations:

Finance Committee – Haidel J. Christophe, Chair; O.C.W. Taylor; Mrs. Hattie John G. Lewis, Jr.; Alfred C. Pierce

Membership Committee – John Guess, chair; Mrs. Fannye Casanave; Roy Weems; Vallery Ferdinand; Raoul J. Maurice, Jr.; Louis Doley; Grover Garron.

Buildings Committee – C. L. Speaker, chair; Alfred C. Pierce; Luther Tanner; Haidel J. Christophe; William Triche; Dave Dennis; Henry Dorsey; Oscar Fischer.

Maintenance Committee – J. W. Merrick, chair; W. G. Boyd; Herman Bush; J. W. Morrell; Charles C. Cochrane; Mrs. Wilbert Drummond.

Operations Committee – John Foster, chair; Leonard Ellis; August Roserio; Herbert Crowley; Miss Helen Badie; Dave Wilkerson; Mrs. Louise Willis.

Constitution Committee – Lawrence A. Young, chair; Rev. A. C. Moore; Mrs. Jessie Vickman; Nolan Marshall; Mrs. Marietta Bertrand; Percy Perkins; Marion Porter; Rev. Avery C. Alexander.

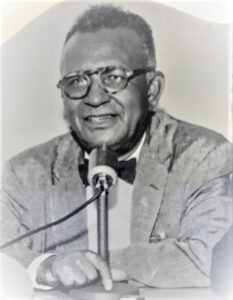

Orlando Capitola Ward Taylor

Ultimately, too few investors produced the funds necessary to make these payments; the purchase agreement was called off and the initial investors reimbursed. In a letter to The Louisiana Weekly published on 31 January 1953, O.C.W. Taylor decried failure of the project as “another evidence of the inability of our inability to cooperate as a group.” Taylor continued, “One of the nasty things about it is the attitude of many of our professional men who make every penny that they earn off the Negro people and yet feel that they are too good to be associated with them in a project of this nature.” The Weekly reported from an unnamed source that a second group would be formed to attempt to bring the project to fruition.

Charles Logan Speaker

By April 1954, the new executive Board held an open house to draw increased interest in the project which yielded more than two hundred excited visitors. The executive officers were Charles Logan Speaker, President; O.C.W. Taylor, Vice-President and Promotional Director; Robert Joseph Van Hook, Secretary; John Bohn Guess, Treasurer; Walter L. Barker and Dave Wilkerson, directors.

O.C.W. Taylor shaking hands with a young man at the open house in April 1954.

Two months later, on 22 June 1954, the Board of Governors met at the summer home of Mr. D’Antoni at Pass Christian and made the final payment on the $225,000 purchase price they had negotiated. In July, the news of the group’s acquisition received national coverage in JET magazine. O.C.W. Taylor hosted Dr. Beverly V. Baranco, Jr., and a group of prominent residents of Baton Rouge at the club that month.

The triumph was short-lived, however. At its meeting on 3 July 1954, the St. Bernard Parish Police Jury (forerunner of the present-day parish council) passed an ordinance banning the operation of any social club, inn, or bar within 3,500 feet of a school. The site of the Crescent City Country Club was just within that radius of the Borgnemouth School, a Black elementary school. Though members of the police jury proclaimed that measure was not driven by racial prejudice, O.C.W. Taylor stated that he knew there was opposition to the club within the parish. Without going so far as to name the official, Taylor stated, “We credit origination of the ordinance to a St. Bernard Parish politician who frankly told us he world oppose a Negro country club.”

In 1958, Mr. Taylor attempted to carry out his vision again, this time on a 6-acre tract in the Pontchartrain Park community. Mr. Taylor’s vision was partially realized with the opening of the Pontchartrain Park Golf Course (renamed for Joseph M. Bartholomew in 1979), for the use of Black golfers in 1956. Prior to that time, Black golfers only had access to the East Course in City Park on Tuesdays and Saturdays as a result of a 1952 agreement by federal Judge J. Skelly Wright. Full integration of the City Park Course did not occur until after the U. S. Supreme Court’s ruling in New Orleans City Park Improvement Association v. Mandeville Detiege in 1958. The officers of the 1958 venture were Belmont Haydel, Sr., President; O.C.W. Taylor, Vice-President; Mrs. Naomi R. Borikins, Secretary; and Olden McCoy Gibbs, Treasurer. The other collaborators were Attorney Benjamin Johnson; Sidney Jordan; Floyd A. Douglas; John H. Blanchard; Elgin J. Hychew; Wesley Jiles; Percy P. Creuzot, Jr.; and Miss Luvenia Dorsey.

Though Mr. Taylor’s dream never materialized, it is worth documenting. His vision and his ability to corral so many business leaders in an attempt to achieve it, is a testament to the leadership of O.C.W. Taylor and the other “race men” and “race women” who forged paths for their people during the long Jim Crow era.

Sources: “Ordinance Aimed at Club, Charge,” The Times-Picayune, 8 August 1954, p. 24. “Abandon ‘Deal’ for Converting River Bend into Country Club,” The Louisiana Weekly, 31 January 1953, p. 1, col. 1 and p. 6, col. 4; “Abandon Plans for Negro Club at Poydras,” The St. Bernard Voice, 13 August 1954, p. 1; “N. O. Group Plans New Country Club,” The Pittsburgh Courier, 20 December 1958, p. 28. The Chicago Defender, “Buy Swank La. Estate for New Country Club,” 26 June 1954, p. 4; “What’s Happening in New Orleans?” 17 July 1953, p. 19; “Palatial Mansion,” 17 April 1954, p. 10; “What’s Happening in New Orleans?” 17 July 1954, p. 20.

Jari C. Honora

I am always pleased to learn more facts about the development of black history and culture of our city. Your research is so important and I do hope todays youth are paying attention especially since newspapers, TV, internet are readily available now but not so much when I was in high school in the 50s. Mr. Taylor was my elementary school principal at Mc 37 on Bienvile(where Wicker is now). Thanks for spelling out the OCW part of his name. He also had a weekly radio program broadcasted from the WMCA.

Were they able to recover their funds spent on the mansion?

Thank you for this monumental verifiable account of the untold truth not broadcast in mainstream media in the 1950s. It underscores the divisive ideology that drives much of what we see today in national politics.

Very interesting, Jari.

I somehow missed this article. There is a part to what happened with the country club which has been missed.

I remember the country club incidents very well. Call me Jari and we will talk about it to see how it fits into what you have researched.