There is an undeniable resolve and spiritedness in the face of the then-22-year-old Frances Smith, who more than 130 years ago traveled from her home on Grand Route St. John to the Frenchmen Street studio of inveterate photographer Aristide Daliet to have her picture taken. The strength conveyed in her photograph is the same strength which later sustained her as she lost her husband and oldest son in less than five months; and as in time, she lived to bury all but one of her nine siblings. Frances’ determination was in no small part inherited from her mother, Sarah Ann Stokes, a survivor of the domestic slave trade, who while Frances was a small child, fought for more than three years in the courts of Louisiana to retain possession of the home in which she reared her ten children. The spacious home on New Orleans’ Columbus Street to which Sarah Ann defended her ownership in the 1860s was a far cry from the harrowing circumstances in which she found herself twenty years before.

The “Forks of the Road,” located about a mile east of Natchez, Mississippi, was notorious as the second largest slave market in the antebellum South. Natchez attorney and Confederate general William T. Martin later described the Forks of the Road stating: “In some years there were three or four thousand slaves here. I think that I have seen as many as 600 or 800 in the market at one time. There were usually four or five large traders at Natchez every winter. Each had from fifty to several hundred negroes, and most of them received fresh lots during the season. They brought their large gangs late in the fall and sold them out by May. Then they went back for more.” One of the enslaved people sold at the Forks of the Road during the winter of 1848 by trader John D. James was fifteen-year-old Sarah Ann Stokes. Described as a mulatress, Sarah Ann was a native of Virginia, from which John D. James sourced most of the human cargo he trafficked at the Forks of the Road. On 31 January 1848, James sold Sarah Ann and a man named James to the Widow Mary Purcell Smith, an English-born orphan who had come to America under the care of the famed Percy family of the Mississippi Delta. Three years later, on 1 February 1851, the Widow Smith sold Sarah Ann by an act under private signature to her son, Elijah Smith, a planter and agent who oversaw the family’s Providence Plantation, about two-and-a-half miles below Natchez.

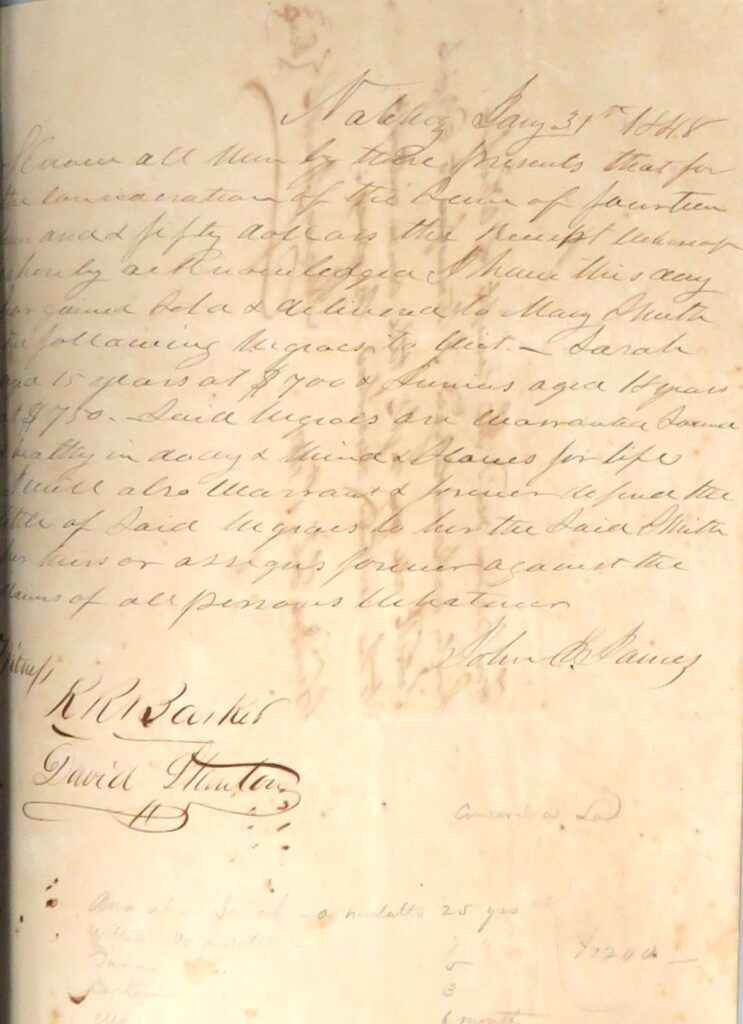

Sale by act under private signature of Sarah (15) and James (18) from slave trader John D. James to Mary (Purcell) Smith, mother of Elijah Smith, 31 January 1848.

That same year (1851), Sarah Ann Stokes gave birth to a son, William Overton Smith, who was fathered by her owner, Elijah Smith. Smith, who was never married, had ten children with Sarah Ann between 1851 and 1867: William Overton; James; Catherine; Alfred; Edward; Henry Wellington; Alice; Anna; Mary Frances; and Marie Eugenie. While business frequently took Elijah downriver to New Orleans, Sarah Ann and her children occupied their own home on Providence Plantation, the Smith family homeplace. On 11 January 1858, after their fourth child was born, Elijah Smith appeared before New Orleans notary Adolphe Boudousquié to manumit Sarah Ann and the children William, aged 7; James, aged 5; Catherine, aged 3; and Alfred, six months). Cognizant of the precarious situation in which his free black partner and their children could find themselves in the event of his sudden death, Smith carefully accumulated assets such as landed property, stocks, and cash, which he ensured were in Sarah Ann’s name.

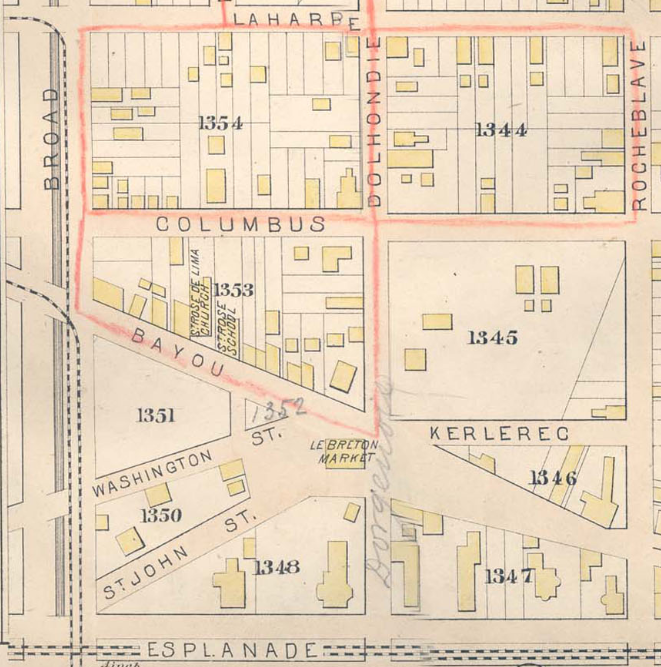

The large home facing Columbus Street just opposite the back of St. Rose de Lima Church was purchased in Sarah Ann Stokes’ name in 1865. (Robinson Atlas, plate 22, 1883)

One of these assets was a house in Algiers on the upriver side of Seguin Street, which Smith bought on 19 December 1861 in the name of Sarah Ann and the then six children. Fearing the prevalence of smallpox on the west bank at the time, on 8 April 1865, he had Sarah Ann to purchase a larger home for their growing family at 365 Columbus Street (later 2539 Columbus) between North Dorgenois and Broad streets. This second home was later the subject of a three-year court battle between Sarah Ann and Elijah’s sister Mary Jane (Smith) Veazie.

In the court proceedings, both sides produced letters from Elijah written to Sarah Ann or to others on her behalf. The majority were addressed to Smith’s business partner, James E. Harris, whom he instructed to read the letters to her and write out her replies. The intimacy and solicitude displayed in these letters offer a glimpse into the relationship between one “bachelor patriarch” and his formerly enslaved partner:

New Orleans March 28/[18]65

Mr. Harris

Dear Sir,

Will you please tell Anne she will have to come down here to sign the purchase of the house, she can come on the Mittie Stephens next Monday with Captain Sherman if she can’t come on that boat she can come on the Pierce she will have to make old Sall come and stay in her house with the children as they could not be left with anybody else. I expect she will have to bring the baby, but she will know best about that, Sall must come to Providence and stay in Anne’s house until Anne get back again she will only have to be here one or two days and I will go back with her to move all the things down but she has to be here, to get the house. I think Sall will be willing to stay and take care of the children while Ann comes down I would not trust anybody else to stay with the children. If Annie thinks she could let the baby stay at home she better do it, but she knows best about that. The Mittie Stephens leaves Natchez at 12 o’clock on Monday. I will send a note to Captain Sherman to bring her down which you will give to her and you go with her to get the pass to come here and returned.

(Signed) Elijah Smith

You can tell Annie I have just bought a house and will let her know by the next boat when I can get possession of it and tell her to be getting the children ready to come down when I write for them. I will make Byron b[r]ing them down – but I don’t know how long the people will be getting out. I will then tell her what things to bring. I wish you would make Bob fix up the carriage horses in fine order to come down please have that well done. I did not promise Gilbert any kind of wood.

March 25th 1865

Respectfully

(Signed) Elijah Smith

New Orleans March 18th/[18]65

Mr. Harris

Dear Sir,

I wrote you last week by the Pierce and sent up 50 sacks of corn and two barrels of mess pork and hope you got it out safe. You must write me by the Pierce every Wednesday. Tell Annie the smallpox is so bad over the river I have not been to the house. I am looking for a place on this side but don’t [know] when I can find one to suit. Tell Annie to send me word by you if she wants to come down now and if she does, I will get a place. I have to be at Natchez by the 1st of April if I can find a man to take Pitts field, but if no one wants it, I have no other business there. Tell Annie to send me word exactly what she wants to do. If she wants to come down I will get a house. You can read this letter to her and she will tell you what to say and reply. Direct your letters to me Care Geo. S. Manderville New Orleans

Respectfully

(Signed) Elijah Smith

New Orleans March 30/65

Mr. Harris

Dear Sir,

I wrote to you by the Grey Eagle and directed the letter to the care of Dr. Page. I suppose you got it and told Annie to come down about the house. Byron need not come with her this time, as I will go back with her and she will only bring the baby and perhaps she will leave that at home with Sal who must go to Providence and stay in Andy’s house to take care of the children. Annie will come on this boat and remain on board until I call for her. Write soon.

Respectfully

(Signed) Elijah Smith

Anne has six hundred dollars in gold which is her own money & not to be disturbed by any person or persons whatsoever.

October 3d 1861

Providence (Signed) Elijah Smith

I have used the above money & my estate must refund it to Anne.

(Signed) Elijah Smith

New Orleans July 11th 1865

Dear Anne,

I sent you a box of groceries by the fashion, and the half barrel of beef goes today (when you open the beef mind & keep the meat under the brine or it will spoil) I send also a little box with a watch for each of the boys and some beads for each of the girls, and I will bring you a handsome present when I come home for your kindness to me when I was sick. I am sorry to go without seeing you all but I hope God will spare us all to meet again, do take care of yourself & the children and keep them out of the sun. I thought best to take all your papers & put them at the notaries Messrs. Gottschalk & Magner who will keep them for you, as you will have to go there when you take up the notes, so he can release the mortgage, he is about the only man in Orleans you can trust, never sign anything unless Mr. Magner tells you. I told him if I never got back, he would have to advise you what to do. He has your title papers, insurance papers, tax papers and certificate for your thirty shares of rail-road stock & a note of Mr. Marshall’s for $500 due December 1st and one of Mr. Minor (W. J.) for $455.40 due just January 23d/66, both belong to you, and you can get Mr. Magner to collect them. I also give you my acct. against Saml Davis, so if I never get back, you will have something to start the world on. God bless you

(Signed) Elijah Smith

[Postscript]

I collected the dividend of the city railroad $180 & send you $120 of it. You better hold on to the interest money as long as you can, I send you $20 in spending money. I hope you will have enough till I come back. Good bye.

E. S.

Cognizant that free people of color were often waylaid during their travels and even forcibly re-enslaved, Smith carefully planned Sarah Ann’s arrivals and departures from the city. On occasion, he had “Byron” to accompany her. This was likely Byron Johnson, the son of Natchez’s famed free colored barber and diarist William Johnson. He deposited the titles to her properties and her stock certificates with notary Selim Magner, whom he cautioned her was “about the only man in [New] Orleans you can trust.” The promissory note which Elijah issued to Sarah Ann and for which he made his estate liable was likely a clever way of ensuring that the mother of his children would receive something upon his death. The forces from which he sought to protect Sarah Ann and the children, included his sole surviving sibling, Mary Jane (Smith) Veazie, who was his only lawful heir.

Elijah Smith died on 23 June 1868 at the age of fifty in his Columbus Street home. Present when he died were Sarah Ann Stokes and his sister, Mary Jane Veazie. That Smith was Sarah Ann’s partner and the father of her ten children was undeniable. In the later court case, planters Alfred V. Davis and George W. Sargent both testified to those facts. Davis described Elijah Smith as “the most intimate friend I ever had,” saying further, “My intimacy with Elijah Smith, deceased, in his life time, was that of a brother.” Alfred Davis also testified that “Defendant [Sarah Ann] was the housekeeper and mistress of Elijah Smith, deceased, during my acquaintance with her, by said Smith acknowledging defendant to be his woman, and that the children by her were his children.” George Sargent corroborated this in his testimony: “I always understood that she was his mistress, from the fact that I heard him acknowledge that defendant’s children were his children.”

If the fact that Elijah Smith had made a natural family with Sarah Ann Stokes was clear to his friends, it was undoubtedly clear to his only surviving sister. The letters from Smith quoted above were either in Sarah Ann’s possession or were turned over to Mary Jane by the Mr. Harris to whom many of them were addressed. Mary Jane knew that aside from their mixed-race and illegitimacy, Sarah Ann’s children were her nieces and nephews.

Like so many antebellum slaveholders, Mary Jane (Smith) Veazie found herself in greatly reduced circumstances following the Civil War. By 1875, her namesake daughter, Mary Jane Veazie, found herself giving concerts to make money and all but a few acres of their home place, Providence, had been sold to Black Republican state legislator John Roy Lynch. On 13 January 1868, seven months after he brother’s death, Mary Jane filed suit in New Orleans’ Seventh District Court asserting that she was the lawful heir to the Columbus Street home and its furnishings which were still in Sarah Ann’s possession. Her contention was that as a domestic to her late brother, there was no way that Sarah Ann could have bought the house and that the money had to have come from him. The court ruled in June 1870 that there was no evidence to prove that Elijah Smith provided the funds with which Sarah Ann bought the house and that there was no evidence that it was a “disguised donation” intended to dispossess the heirs of his estate. In November 1870, Mary Jane appealed to the Supreme Court of Louisiana, which affirmed the lower court’s decision in April 1872.

Sadly, Sarah Ann lost the home just a year-and-a-half later due to the debt she ran up in back insurance. She moved her large family to the home they rented at what is now 2905 Grande Route St. John. Of her nine children who lived to adulthood, all but one married or entered into long-term relationships. When 22-year-old Mary Frances Smith, who was called “Fannie” as a nickname, went to have a cabinet card with her likeness made at Daliet’s studio on 6 May 1888, it likely marked her entry into young womanhood. Two-and-a-half years later on 29 November 1890, she married a neighbor, Louis Lopez, the son of Professor Manuel Lopez and Eugenie Brugier. Louis worked as a drayman and for a time as a weigher with the U. S. Customs Service. They owned their home at 2913 Maurepas Street, which remained in their family for many decades. Louis and Fannie had four children, all but the last of whom, her mother Sarah Ann Stokes lived to see born. Sarah Ann died of pneumonia at the age of sixty-five on 6 January 1897 at 2905 Grande Route St. John. She was interred in the family coping in St. Louis Cemetery No. 3, where many of her children and grandchildren are also buried.

Louis and Fannie’s children were: Louise Vera (Lopez) Gross (15 March 1892-31 August 1971); Leona Theresa (Lopez) Monroe (8 November 1893-16 March 1975); Robert Percy Lopez (11 December 1895-16 July 1919); and Alfred Joseph Clyde Lopez (11 January 1901-17 July 1986). Louis Lopez, Fannie’s husband of twenty-eight years, died on 13 January 1919. Fannie’s oldest son, Robert Percy Lopez, named for the benefactor who brought his orphaned great-grandmother from England, served with the all-Black 365th Infantry Regiment in France during World War I. He survived battle and was honorably discharged on 19 March 1919, only to die four months later on 16 July 1919, at 23 years old.

With the passage of the years, Mary Frances (Smith) Lopez witnessed each of her siblings as they were carried to their final resting place: Alfred Smith in 1896; James Smith in 1898; Catherine (Smith) Gonzales in 1900; Alice (Smith) Hilaire in 1913; Henry Wellington Smith and William Overton Smith in 1915; Marie Eugenie (Smith) Penn in 1931; and finally Anna (Smith) Vauquelin joined them all in 1951.

Mary Frances (Smith) Lopez died on Saturday, 6 July 1946, at the age of eighty. Her funeral was held in Saint Rose de Lima Church on Bayou Road. She was interred in St. Louis Cemetery No. 3 on Tuesday, 8 July 1946. These details of her life and her family story might have gone unrecorded had her photograph not caught our attention. It is among those preserved in Xavier University’s Archives Photograph Collection, which is an artificial collection, that is, one pulled together by the archival staff – in this case an assortment of photographs of people, groups, and institutions mostly from New Orleans and south Louisiana.

Jari C. Honora

Sources: “Francis Smith Lopez” Portrait, 6 May 1888; Archives Photograph Collection, Xavier University of Louisiana Archives & Special Collections, New Orleans; cabinet card with imprint Aristide Daliet Cabinet Studio, 31 & 33 Frenchmen St., New Orleans. Louisiana Supreme Court, No. 2993, Mrs. M. J. Veazie v. Sarah Ann Stokes, April 1872; University of New Orleans Louisiana and Special Collections, Earl K. Long Library. Fannie Smith obituary, The Times-Picayune (New Orleans), 8 July 1946, p. 4, col. 7. Acts of Adolph Boudousquié 16: p. 19-20, Manumission of Sarah Ann and her children by Elijah Smith, 11 January 1858; Notarial Archives, Clerk of Civil District Court Land Records Division, New Orleans. Bertram Wyatt-Brown, The House of Percy: Honor, Melancholy and Imagination in a Southern Family (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 60. Orleans Parish, Louisiana, Marriages Licenses Returned, 27:186, Louis Lopez-Mary F. Smith, 29 November 1890. Find A Grave, database with images (http://www.findagrave.com), memorial 131767239, Sarah N. Vauquelin, St. Louis Cemetery No. 3, New Orleans, Orleans Parish, Louisiana; grave photograph by Ancestors (contributor 48410496). Robinson’s Atlas of the City of New Orleans, Louisiana (New York: E[lisha] Robinson, 1883); digital image, Plate 22, sq. 1354; New Orleans Notarial Archives, Clerk of Civil District Court Land Records Division (https://www.orleanscivilclerk.com/robinson/atlas/robinson22.html#). Frederic Bancroft, Slave Trading in the Old South (1931; reprint, Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2023), 304-305.

Interesting piece.

One of the most outstanding persons that I have ever encountered in my years as a teacher. We women of color are smart and brave.

Incredible history, documented, for all future generations to read!

Thank you for this remarkably detailed story. The implied and factual descriptions speak volumes about relationships, culture, and compassion openly displayed by some very courageous people.

I agree with you, sir. She was truly remarkable.

My grandmother grew up on the Bayou St. John among her relatives. Her great grandfather, Celestin Darby, lived on Maurepas St. next to the Pierry family. Her maternal grandparents, Arnaud Sarrazin and Victorine Darby Sarrazin lived at 3035 Grand Route St. John. The majority of her family lived in the neighborhood and owned their homes. They attended St. Rose De Lima Church. Saying this, my ancestors knew the Lopez family. Clyde Lopez was a witness to the marriage of Dave J. Snaer and Leontine Patin in 1938. Leontine Patin was my grandmother’s first cousin.

Hello there- when did Celestin live on Maurepas? I am looking at some girls there in the 1920s.

Would you say it was a predominantly Creole People of Color living there?

Celestin Darby, his siblings and their children lived on the Bayou St. John from maybe 1840s. Celestin died in 1902, however, one of his daughters lived in his home. My great grandmother, Marie Francois aka Francis and her husband and children ( one being my grandmother lived in the Bayou until 1922. My Sarrazin family also lived in the Bayou. A Sarrazin married a Darby. Yes, the Bayou at one time was a community of Creoles of Color.